读亨利•格拉西《十八世纪文化进程》

郭越若

亨利•格拉西 (Henry Glassie),民俗学家、人类学家、教育家、作家。1941年3月24日出生,曾在五大洲进行过实地考察,并撰写过有关民俗各个方面的书籍,从戏剧、歌曲、故事到工艺、艺术和建筑。格拉西于1970年开始在印第安纳大学民俗研究所任教。1976年,他成为宾夕法尼亚大学民俗与民俗生活系主任。1988 年,他回到印第安纳大学担任学院教授,教授民俗与民族音乐学、美国研究、中欧亚研究、近东语言与文化以及印度研究。格拉西于1961年开始对南阿巴拉契亚地区的歌曲、故事和建筑进行实地考察。此后,他在美国多个地区以及爱尔兰、英国、瑞典、意大利、土耳其、巴基斯坦、印度、孟加拉国、中国、日本、尼日利亚和巴西进行了实地考察。

格拉西在1968年出版了他的第一部学术著作《美国东部物质民俗文化的模式》。该书脱离常规的以时间为坐标的传统研究方法,以地理学关注地域空间分布的方法研究物质文化的变化,包括风土建筑,或以风土建筑为主导进行分析。格拉西首次用区域空间的概念,将地域中间不同类型的物质文化综合在一起观察分析,打破长期以来围绕物质文化研究的障碍。他首次尝试比较各种物质民俗文化,包括建筑、工具甚至烹饪等,以发现它们共同的模式,并以此挑战民俗文化和美国文化研究的传统观点,如移民们从欧洲大陆带来的传统生活习惯文化习俗如何在当地的特殊自然条件下,与当地的传统文化相结合而产生新形态、新风格。他还探讨了大众文化与民间文化的互动规律,以及如何界定民间创作与商业和大众创新。这些在当时都属于非常前瞻的尝试。《美国东部物质民俗文化的模式》依次在考古学界、地理学界、美国文化研究领域及人类学和民俗学界引起关注和赞誉。格拉西强调表达风土建筑随自然及社会环境的变化而与之的互动:稳定与变化;正式与混杂;环境与反控;时间性与区域性。

本文依据作者于1961年至1970年在美国东部进行的田野调查写成,发表于1972年。风土建筑结构主义分析的方法论是格拉西在20世纪70年代的主要成就:既突破了传承已久的由伊沙姆时代建立的风土建筑类型研究的框架,又以跨学科的科学研究的严谨态度进入了建筑学术主流。将金博尔的二分法—学术与风土,转换到范式研究的实践。这一跨学科的大胆挑战,将建筑史学方法论研究大大地推进了一步,如:转换语法和社会语言学,以构建民俗设计过程和方言形式曲目变化的几何模型;以结构主义者的文化概念来定义乡村建设者们从开放到封闭观点的心路历程等。在此之后,风土建筑研究随着学术界宏大叙事范式的逐渐消亡,结构主义研究范式逐渐离开主流研究领域,强调微小叙事、主观体验,挑战普世法则,去中心化反二元论的潮流迎合了解构主义的内涵。此后格拉西自己也成为这一方面的学术带头人。他的众多学生和志同道合者不断地实践并出版大量的文章和书籍,扩展与其他学科的交融,重新定义了许多关于历史、文化、传统、艺术、美学、风土建筑、物质文化等概念。

本文通过对18世纪特拉华地区河谷民间建筑的研究,揭示了该地区文化的演变进程。在正文开始前,格拉西先将自己的研究方法娓娓道来。区别于通常的聚焦文本的研究方式,格拉西采用了一种基于物件的研究方法,因为对过去的人而言,文字是少数识字的人的专利,聚焦文本的研究注定将大部分普通民众排除在研究范围之外。在选取研究物件时,学者通常会出于现代化的标准或是选择特定的特殊的物件,对此,格拉西提出了自己的选取标准,主要有三:容易建立与时间和地点的联系、足够复杂、有足够多的材料,房屋正是最符合这三条标准的物件之一。格拉西所说的房屋时数量上占主导的简陋的民间房屋,并且他的关注点在房屋的基本形式,即内部使用空间,而非建筑外观。

在地理维度上,本文的研究范围为特拉华河谷下游地区;在时间维度上,本文的研究聚焦十八世纪中后期,这是一个创造与融合的时期。本文主要研究了两种建筑类型:房屋与农场规划。在房屋方面,从英格兰传入的乔治亚式房屋在18世纪开始在当地盛行,根据实用与环境的需要,当地人对其进行了改造,如扩大与缩减。与此同时,乔治亚式房屋与当地传统民居的融合诞生了两种新的房屋类型:烟囱偏离中心的房屋和“I”型房屋。在农场规划方面,传统英格兰的紧凑布局在传入美国后发生了变化,产生了新的布局类型,如:方形内院的布局、松散的布局等。影响农庄规划的因素有很多,如矩形或线性平面的理想模式、道路的方向、地形、向南的朝向等。

两种建筑类型的转变实则展现处当地人面对外来文化完全不同的态度。在房屋中,当地人尝试在保留内部空间布局的基础上,将乔治亚式风格房屋的外观融入当地传统民居中,展现出面对外来文化时好奇、追求时髦但又谨小慎微的保守态度;而在农场规划中,当地人则根据地形、河流、道路走向等条件,对英格兰传统紧凑布局进行了大胆的改变,展现出无畏的冒险精神和对美好生活的追求。正如格拉西在最后一段描写的那样:十八世纪特拉华河谷的普通人是一个个人主义者,但也是一个循规蹈矩的人——一个警惕的冒险家。他在适应时代变迁的过程中感到焦虑不安,因此选择在保守的同时显示现代意识。

十八世纪文化进程

亨利•格拉西

郭越若 译 潘玥 校

The people of the past wrote little. A progressive agriculturist may have left a diary in a trunk for modern discovery; an egotistic public servant may have endured his sunset years longhanding reminiscence, but most of those who are now dead wrote formally about themselves no more than people do today. Like us, they allowed posterity to depend on the external observer for a record of their thought. Reliance on the journalist or the literate elite for our glimpses of deceased cultures skews our view of the past in a definite direction— the direction formalized in those history texts to which the intellectual reformer and the black spokesman for today’s minorities object. Reading the words of the past, we can accumulate the fragments for a fair mosaic of the life of the wealthy, which they and their literate retainers bequeathed to us, and we can uncover occasional references, usually maddeningly superficial, to workaday life in the chancy journals of travelers. The comments of an Andrew Burnaby or a Pehr Kalm are invaluable, but we have been left no understanding of the culture of the majority: those who farmed or tinkered with sufficient success—the kind of people who now live in modest, solid brick houses, drive a late rhythm of “The Secret Storm”; just folks who are more excited by the World Series than they are by the latest show at Museum of Modern Art.

过去的人很少写作。一位进步的农学家可能会在箱子里留下一本日记,供现代人发现;一位自负的公务员可能会在夕阳西下的岁月里长篇大论地回忆往事,但大多数已故的人正式写下的关于他们自己的文字并不比今天的人多。和我们一样,他们让后人依靠外部观察者来记录他们的思想。依靠记者或文人精英来窥探逝去的文化,会使我们对过去的看法朝着一个明确的方向偏移——知识改革者和当今少数民族的黑人代言人所反对的那些历史文本中正式确定的方向。阅读过去的文字,我们可以为富人及其识字的家臣遗留给我们的富人生活场景积累碎片,形成一幅美丽的马赛克图画,我们还可以在旅行者的奇特日记中偶尔发现对日常工作生活的提及,这些提及通常肤浅得令人抓狂。安德鲁.伯纳比或佩尔.卡尔姆的评论非常有价值,但我们却无法了解大多数人的文化:那些耕种或修补并取得足够成功的人——他们现在住在简朴、坚固的砖瓦房里,开着过时的轿车,随着”秘密风暴”的节奏打扫房间;相比现代艺术博物馆的最新展览,他们对世界大赛更兴奋。

Today, the average person is a consumer; in the eighteenth century he was a maker. If he left no books, he did leave artifacts by the thousands. The wagon or the rifle or the shape of a field outlined by walls of rock is as direct an expression of culture as the book—all are artifacts. These artifacts, many now inflated in value as antiques, have attracted different sorts of scholars. Some, trained as historians, have selected a few things associated with specific events—a blood stained chair from Ford’s Theater, say—to use as visual props for historical notions set in print. Others have treated objects as if they were art, selecting the few which measure up to modern taste and arranging these about the walls of museums in chronological schemata to illustrate the sequence of detail called “style.” Selection on the basis of contemporary need has demonstrable social worth, whether it is mythological (in the case of the historian striving to justify the current situation) or aesthetic (in the case of the antiquarian working to preserve some old-fashioned charm in a drab and jerry-built present); but as scholarship it is incomplete, and incompleteness is wrong—except by accident.

今天,普通人是一个消费者;而在十八世纪,他是一个制造者。即使他没有留下书籍,他也会留下成千上万的物件。马车、步枪或岩壁上勾勒出的田野的轮廓,与书籍一样,这些都是文化的直接体现——这些都是物件。这些物件(其中的许多被视为文物而价值倍增)吸引了不同类型的学者。一些受过历史学训练的学者选择了一些与特定事件相关的物品——比如,福特剧院里一把沾满血迹的椅子,作为印刷品中历史概念的视觉道具。其他人则把物品当作艺术品来对待,挑选出少数符合现代品味的物品,按时间顺序排列在博物馆的墙壁上,以说明被称为”风格”的细节顺序。根据当代需要进行的选择具有明显的社会价值,无论是从神话角度(历史学家努力证明当下的合理性)还是从美学角度(古物学家努力在单调而粗制滥造的今天保留一些旧式的魅力);但作为学术研究,它是不完整的,而不完整是错误的——除非是偶然情况。

A methodological limitation to print binds the scholar to studying only the handful of people who were literate. The artifact is potentially democratic; artifacts from the past are so abundant that they can be utilized to replace romantic preconceptions with scientifically derived knowledge. This is not, however, inevitable. Often the historian treats only the genealogically relevant things, artifacts which fit the scheme of progress.

印刷品在方法上的局限性使学者只能研究少数识字的人。物件具有潜在的民众性;过去的物件非常丰富,因此可以利用它们,以科学知识来取代浪漫的成见。然而,这并非不可避免。历史学家往往只处理与谱系相关的事物,即符合进步计划的物件。

To parody Herbert Read’s statement on art history, the history of artifacts is often presented as a line from progressive thing to progressive thing. The usual historical treatment of agricultural implements, for example, is not a description of the tools in use at given times and places; rather, it is a chronological list of rare tools that suggests the “evolution” of modern machinery. This constrictively linear approach to the past, as Claude Lévi-Strauss has shown in his magnificent book, The Savage Mind, leaves most people and most artifacts out of consideration.

为了模仿赫伯特.雷德关于艺术史的论述,物件的历史往往被表述为一条从进步事物到进步事物的直线。例如,通常对农具的历史学的处理,并不是描述特定时间和地点使用的工具,而是按时间顺序列出罕见的工具,暗示现代机械的”进化”。正如克劳德.列维-斯特劳斯在其巨著《野性的思维》中所指出的那样,这种对待过去的存在局限性的线性方法将大多数人和大多数物件排除在考虑范围之外。

A similarly ethnocentric approach treats past artifacts only if they are judged appealing by contemporary standards. The prevailing opulent taste of most critics causes them to single out some things as better than others on the basis of their richness of decoration. The application of modernist aesthetic criteria to past artifacts causes a violent change; it eliminates from greatness the things that are untrue to their media. Chippendale highboys and Gothic cathedrals are banished (both have characteristics appropriate to sculpture rather than to furniture and architecture), and their places in art appreciation classes are taken by milking stools and the stone cabins of the Hebrides. Taste is an important subject for study, but the modern critics’ evaluations teach not of past but of present culture. Connoisseur-ship and the optimistic notion of progress have prevented the study of artifacts from becoming a means for making history the rigorous study of past cultures.

只有当过去的物件被当代标准评判为具有吸引力时,类似的以种族为中心的方法才会对其进行处理。大多数评论家的普遍的奢华品位会让他们根据装饰的丰富程度,认为某些物件比其他物件更好并将它们挑选出来。将现代美学标准应用于过去的物件引起了剧烈的变化;它将不符合其媒介的物件从伟大中剔除了。

Some scholars—they may be historians, archaeologists, cultural geographers, anthropologists, or folklorists—have begun to appreciate the artifact as a powerful source of information. They view objects as books that, no matter how pretty the bindings, are worthless until read. A hammer and a quilt may look nice behind the museum’s glass, but they are merely chance associations of hard or soft substances unless enough is known about their source and function to make accurate interpretation possible. A building may enhance the landscape, but it remains a heap of old wood and stone until it is analyzed. The analysis leads away from a concern with the fabric itself toward the ideas that were the cause of the fabric’s existence. Strictly speaking, the ideas in the mind of a maker can never be enumerated, but the scholar can venture near a comprehension of the mind’s activities and the maker’s intent through deep play with components, sources, and models of process, as John Livingston Lowes did in his study of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s two greatest poems. From sticks of wood joined into a chair, from the burned clay mortared into a dwelling, we can get an idea of ideas, a feeling for the concepts that are culture, an understanding, perhaps, of the anguish and pleasure, the joy of innovation and the pain of compromise of men long dead.

一些学者——他们可能是历史学家、考古学家、文化地理学家、人类学家或民俗学家——已经开始将物件作为一个强大的信息来源来欣赏。他们将物件视为书籍,无论其装订多么精美,在阅读之前都是毫无价值的。在博物馆的玻璃后面,一把锤子和一床被子可能看起来很美,但它们只是软硬物质的偶然组合,除非对它们的来源和功能有足够的了解,并且有可能做出准确的解释。一座建筑可能会美化景观,但在对其进行分析之前,它仍然是一堆陈旧的木头和石头。分析会将人们从对织物本身的关注引向导致织物存在的想法。严格说来,制作者头脑中的想法永远无法一一列举,但学者可以通过对组成部分、来源和加工模式的深入研究,大胆接近对心理活动和制作者意图的理解,正如约翰利文斯顿-洛斯在研究塞缪尔.泰勒.柯勒律治最伟大的两首诗时所做的那样。从木条拼接成的椅子上,从烧焦的粘土砌成的居所中,我们可以领悟到思想,感受到文化的概念,或许还能了解到逝去已久的人们的苦恼和快乐、创新的喜悦和妥协的痛苦。

The spoor of culture on the land is amazing and easily followed. The dangers in interpreting from artifact back through behavior to culture are obvious, but it is the best means we have; we will never understand the eighteenth century if we read only books. By reading artifacts, if we will read enough of them and not be trapped by a shapely cabriole leg or a scrap of molding, we can learn of past culture, the repertoire of learned concepts carried by those people who framed not only our basic law, but our environment and social psychology as well.

这片土地上的文化足迹令人惊叹,而且易于追踪。从物件通过行为回溯到文化的危险是显而易见的,但这是我们所拥有的最好的方式;如果我们只读书籍,我们将永远无法理解十八世纪。如果我们能读到足够多的物件,而不是被一条修长的家具腿或线脚所困住,我们就能通过阅读物件了解到过去的文化,了解到那些不仅制定了我们的基本法律,而且还制定了我们的环境和社会心理的人们所携带的一系列学问概念。

In using things to teach of the past, some classes of artifacts are more useful than others. This usefulness is a function of the ease with which objects can be related to their time and place, of a complexity sufficient to eliminate the probability of polygenesis, and of the existence of enough material to prevent theory from being built on chance survival. Architecture—complex objects that can be sensed inside and out and are such direct and conscious expressions of culture that for both scholar and builder they become symbol—is one of the most useful kinds of objects.

在利用事物来讲述过去时,某些类别的物件比其他类别的物件更有用。这种有用性取决于物件是否容易与其所处的时间和地点联系起来,其复杂程度是否足以消除多基因的可能性,以及是否有足够的材料来防止理论建立在偶然的生存基础上。建筑——可以从里到外感知的复杂物体,是文化的直接和有意识的表达,对于学者和建造者来说,它们都是象征——是最有用的物件类型之一。

This paper deals with two matters of Delaware Valley architecture—houses and farm plans. It is based on fieldwork conducted in the eastern United States between 1961 and 1970. It is intended not as a study but as a metaphor for a study. The paper itself is an abstraction, an impression of study based on social-scientific rather than art historical philosophy. It does not include the kind of information normally presented in art historical publications but is made of the stuff familiar to readers of cultural geographic or folkloristic publications. It is offered in this context to increase understanding and communication and to illustrate an alternative to art historical considerations of vernacular architecture and is intended not to replace but to complement. The full study of a subject as large as building in the Delaware Valley should involve the art historian’s emphasis on diachronic methodology, concentrating on the few fine houses and public buildings remaining and on the decorative elements of a dwelling’s facade. It should also involve the social scientist’s emphasis on synchronic methodology, focusing on the quantitatively dominant humble buildings, and on the economic functions of a building’s internal volumes.

本文涉及特拉华河谷建筑的两个方面——房屋和农场规划。本文基于1961年至 1970年期间在美国东部进行的实地考察。本文的目的不是作为一项研究,而是作为一项研究的隐喻。文章本身是一份摘要,是基于社会科学而非艺术史哲学的研究的印象。它不包括艺术史出版物通常提供的信息,而是由文化地理或民俗学出版物的读者所熟悉的内容构成。在此背景下,本手册旨在增进理解和交流,并说明对风土建筑的艺术史视角考量之外的另一种选择,其目的不是取代,而是补充。对特拉华河谷建筑这样一个大课题的全面研究,应该包括艺术史学家所强调的非同步方法论,集中研究现存的少数精美房屋和公共建筑,以及住宅外墙的装饰元素。它还应该包括社会科学家所强调的同步方法,重点关注在数量上占主导地位的简陋建筑,以及建筑内部容积的经济性功能。

The attempt to account for all building is fundamental to the social scientist’s approach to architecture. When the totality of building is taken into account, the mansions and gems considered worthy of preservation form such a tiny portion of the whole that they deserve little attention. Similarly, by considering all of each building, crockets, brackets, and twitches of stylish trim become unimportant when compared with matters of basic form. The architect Clovis Heimsath expressed the notion succinctly in his intriguing book on Texas architecture. “It’s the form that really counts in architecture. Decoration buzzes around the form to dress it up.”

试图对所有房屋作出解释是社会科学家研究建筑的基本方法。当考虑到全体房屋时,被认为值得保护的豪宅和珍宝在整体中只占很小的一部分,因此它们不值得关注。同样,如果考虑到每栋建筑的整体性,那么与基本形式相比,钩饰、托架和时尚的装饰就变得不重要了。建筑师克洛维斯.海姆萨斯在其关于德克萨斯州建筑的有趣著作中简明扼要地表达了这一观点。”在建筑中,形式才是最重要的。装饰则是围绕着形式进行的”。

It is easy and voguish but incorrect to think of these basic forms as following function (folk buildings frequently have a Bauhaus clarity, which calls to mind the functional style of recent architecture). The basic forms were useful; people lived and worked in them, and they did function—to return to the anthropological sense of the word—both economically and aesthetically. But they were not designed to suit idiosyncratic need; they were traditional components, traditionally structured into traditional organizations of space required for psychological comfort. The forms lay in the minds of their makers until some problem caused them to be drawn out. When drawn out, the forms were defined by some material, stone, log, or brick, frame filled or other, distinct forms added onto it. Forms are types—plans for production—and buildings are examples of types or composite types. It is definitively characteristic of folk buildings, and most buildings are folk buildings, to be examples of types that persist with little change through time. The invariant aspects of a form are the aspects of deepest necessity to the people who must use the form.

把这些基本形式看作是功能性的,这很容易,也很时髦,但却是不正确的(民间建筑常常具有包豪斯式的清晰度,这让人想起近代建筑的功能主义风格)。这些基本形式是有用的;人们在其中生活和工作,回到人类学的意义上,它们确实在经济和美学上发挥了作用。但是,它们并不是为了满足特殊需要而设计的;它们是传统的组成部分,是以传统方式营造出的心理舒适所需的传统空间组织。这些形式一直存在于建造者的脑海中,直到出现问题,才会被绘制出来。在绘制出来后,形式由某些材料定义,石头、原木或砖块,框架填充或镶边。然后,形式可能会被装饰镶嵌起来,也可能会被添加上其他不同的形式。形式就是类型——生产计划,而建筑就是类型或复合类型的实例。民间建筑(大多数建筑都是民间建筑)的明确特征是,它们是类型的典范,历久弥新,变化不大。形式的不变性是指对必须使用该形式的人来说最深层次的必要性。

This paper, accordingly, will concentrate on basic folk types and will be concerned more with architecture as internally usable space than as externally viewed art. A democratic examination of Delaware Valley building leads to a series of conclusions about the cultures of the area during the eighteenth century. These will be exemplified through an examination of certain forms, but the major regional patterns are sketched here as forewarning.

因此,本文将专注于基本的民间类型,并将更多地关注作为内部可用空间的建筑,而不是作为外部观赏艺术的建筑。通过对特拉华河谷建筑的深入研究,可以得出一系列有关十八世纪该地区文化的结论。这些结论将通过对某些形式的研究来体现,但主要的地区模式将以预兆的形式在此勾勒出来。

Since Fred Kniffen’s classic paper, “Louisiana House Types,” scholars have used folk architecture to suggest spatial patterning in the United States. Fieldwork reveals that the Delaware River runs through two major American cultural regions. The Delaware Valley is divided horizontally at about the southern limits of the Pocono and Kittatinny mountains; the portion above this line belongs with New England and New York in the broad culture region of the North, the portion below fits into the Mid-Atlantic, the architectural region including southern Pennsylvania and parts of adjacent Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey. There is an approximate consensus on the regional boundaries among scholars from different disciplines working with different manifestations of culture. The Mid-Atlantic architectural region outlined on the accompanying map is quite similar to Midland speech areas seven and eight in Hans Kurath’s A Word Geography of the Eastern United States. The northern border is in close agreement with that on the map, “Folk Housing Areas: 1850,” recently offered by Kniffen. On the southern and western boundaries there is less general agreement, though the line through southern Maryland is compatible with the one drawn by Wilbur Zelinsky after studying several different cultural traits. Though some of the disagreement in the various maps of cultural phenomena is the result of a difference of interpretation, most of the apparent disagreement results from the distributional differences exhibited by varying aspects of culture. Alan Lomax’s map of the English language folk song styles of North America locates the southern boundary of the cultural region of the North far south of the line in figure or the divisions made by Kurath or Kniffen. This reflects the actual state of difference in the spatial patterns of dialect and folk architecture as opposed to song and fiddle style. The differences in the cultural maps of supposed national homogeneity.

自弗雷德.克尼芬的经典论文《路易斯安那州的房屋类型》发表以来,学者们一直利用民间建筑来暗示美国的空间格局。实地考察显示,特拉华河流经美国两大文化区域。特拉华河谷大约在波科诺山脉和基塔廷尼山脉的南部界限处被水平分割开来;这条线以上的部分与新英格兰和纽约州同属广阔的北方文化区,线以下的部分则属于中大西洋,即包括宾夕法尼亚州南部以及马里兰州、特拉华州和新泽西州部分邻近地区在内的建筑区。不同学科的学者在研究文化的不同表现形式时,对区域界限有一个大致的共识。附图中勾勒出的大西洋中部建筑区域与汉斯.库拉特的《美国东部文字地理》中的第七和第八语言区域十分相似。北部边界与克尼芬最近提供的 “1850 年民间住宅区 “地图上的边界非常吻合。在南部和西部的边界上,虽然与威尔伯.泽林斯基在研究了几种不同的文化特征后绘制的穿越马里兰州南部线相吻合,但总体上却不太一致。虽然各种文化现象地图中的一些分歧是由于解释的不同造成的,但大部分明显的分歧是由于文化的不同方面所表现出的分布差异造成的。艾伦.洛马克斯绘制的北美英语民歌风格地图将北方文化区域的南部边界定位在图中的界线或库拉斯或克尼芬的划分线以南。这反映了方言和民间建筑与歌曲和提琴风格在空间模式上的实际差异状况。与真正惊人的相似之处相比,迄今为止所提供的东部文化地图上的差异是微不足道的。文化区域是有科学依据的,即使在所谓的民族同一性时代,它们也可以被清晰地划分出来。

The lower Delaware Valley, an area, dominated by Philadelphia, that fits into the Mid-Atlantic region, will be the focus of this paper. The lower valley’s areas of close cultural connection are found throughout the remainder of the Mid-Atlantic region. The Mid-Atlantic region has been defined by compromising the distribution of major architectural forms and techniques of construction: for example, north of the region, log construction is rare; the Dutch barn found nearby in New Jersey and New York is generally absent from the region; and the external west British chimney, which is characteristic of areas south of the region, is restricted to a handful of examples in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and in the Alleghenies. The boundaries of the regions are not arbitrary lines scratched through the border country between influential centers. Locations within a region, even when greatly separated, are culturally more alike than juxtaposed locations in different regions. Still, the culture of the Mid-Atlantic exhibits certain extraregional connections, especially between central New Jersey and Long Island, between southern New Jersey and the Chesapeake Bay area, and among southeastern Pennsylvania, central Maryland, and the Valley of Virginia.

本文的重点是特拉华河下游谷地,该地区以费城为主,属于中大西洋地区。下河谷地区与中大西洋地区的其他地区有着密切的文化联系。中大西洋地区是根据主要建筑形式和建筑技术的分布来界定的:例如,在该地区以北,原木建筑非常罕见; 在新泽西州和纽约州附近发现的荷兰谷仓在该地区普遍不存在;而该地区以南地区特有的英国西部外部烟囱仅限于宾夕法尼亚州切斯特县和阿勒格尼山脉的少数例子。地区的边界并不是在有影响力的中心之间的边界区域随意划定的。地区内的不同地点,即使相距甚远,在文化上也比不同地区的并置的地点更为相似。尽管如此,中大西洋地区的文化仍表现出一定的区域外联系,尤其是新泽西州中部与长岛之间、新泽西州南部与切萨皮克湾地区之间,以及宾夕法尼亚州东南部、马里兰州中部和弗吉尼亚山谷之间的联系。

Also, the region is not perfectly homogeneous; it can be divided and subdivided into subregions by plotting the distribution of traits restricted to but not found throughout the region, by establishing the local proportions of traits found everywhere in the region, and by examining the difference in association and significance of regional traits. For example, the drive-in corncrib, called “old fashioned” in Radford’s Practical Barn Plans, is found for the length and breadth of the Mid-Atlantic region, but it is more common in some areas than in others and is treated differently in the subregions. In New Jersey the drive-in corn-crib is a major farm building located in a position of importance within the farmyard; it is fitted with doors and sheds and serves multiple purposes, such as implement storage. In Pennsylvania it is a dependency of the barn, generally located to one side of the barn’s ramp; it often lacks sheds, occasionally, the doors, and frequently serves only as a corncrib. In the Midwest the drive-in corncrib is a large building with a cupola, and in the southern Appalachian region it is a small structure frequently built of logs.

此外,该地区并非完全同质;通过绘制仅限于该地区但并非整个地区都有的特征分布图、确定该地区各处都有的特征在当地的比例,以及研究地区特征在关联性和重要性方面的差异,可以将该地区划分和细分为若干子地区。例如,在拉德福德的《实用谷仓计划》,中被称为”老式”的驶入式玉米仓在整个大西洋中部地区都有发现,但在某些地区比在其他地区更为常见,在子地区中也有不同的处理方式。在新泽西州,驶入式玉米仓是一种主要的农场建筑,位于农田的重要位置;它配有门和棚子,有多种用途,如工具储存。在宾夕法尼亚州,它是谷仓的附属建筑,一般位于谷仓斜坡的一侧;它通常没有顶棚,偶尔也没有门,通常只用作玉米仓。在中西部地区,驶入式玉米仓是一个带有圆顶的大型建筑,而在南部阿巴拉契亚地区,它是一个小型建筑,通常用原木建造。

Paradoxically, although the Delaware River is the threshold of the Mid-Atlantic, it also amounts roughly, to a boundary between the major Mid-Atlantic subregions, separating the almost wholly English New Jersey sphere from the syncretistic British and Germanic Pennsylvania sphere. But there are major intrusions across the river, so that in western New Jersey around Phillipsburg, Pennsylvania characteristics are in evidence, and parts of Chester, Delaware, and New Castle counties are as English as the country to the east. The observable pattern is readily explainable by settlement history, but settlement history might not suggest that this river is as neat a regional border as contemporary fieldwork reveals it to be.

矛盾的是,虽然特拉华河是中大西洋的门槛,但它也大致相当于中大西洋主要子地区之间的分界线,将几乎完全英国化的新泽西州与英国化和日耳曼融合的宾夕法尼亚州分隔开来。但是,一些重要的影响也会跨越河流侵入对岸,因此在新泽西州西部菲利普斯堡附近,宾夕法尼亚州的特征显而易见,而切斯特县、特拉华州和新卡塞尔县的部分地区则与东部地区一样具有英国特色。这种可观察到的模式很容易用定居史来解释,但定居史显示,这条河可能并不像当代实地考察所揭示的那样,是一条整齐的地区边界。

In viewing the Delaware Valley from the other organizational coordinate, time, it is possible to distinguish distinct building phases. By focusing on decorative detail, the architectural historian can chop the past into a lengthy and complicated series of style periods. Most buildings were completely unaffected or only superficially affected by the sequence of “style,” so only three major phases emerge from a consideration of the totality of building. The first, lasting in the Mid-Atlantic area from the period of first settlement to about 1760, was a time of ethnic solidarity in architecture, of the retention of diverse Old World forms and technics with a resultant heterogeneity on the land. The second major time segment included an initial acceptance of new ideas and a blending of the old and new to create a New World repertoire with resultant regional homogeneity on the land. The point at which the regional culture lost its dominance in building practice (though it is nowhere entirely dead and its manifestations still rule the environment) varies from region to region. R. W. Brunskill writes that the end of English regional building can be marked by the coming of the railway in 1840. About the same date seems to hold for the northeastern United States. In the Mid-Atlantic area, regional building practices were retained more tenaciously, and it was not until the era of the First World War that the regional culture was dissolved into the national. In the South the date was still later. Temporally this paper will focus on the early part of the second building phase—the time of extensive and intensive innovation—the third quarter of the eighteenth century; for better than a century later, its legacy was the stable pattern of Delaware Valley building, and the patterns that continue to characterize the landscape today are the products of cultural clash and mesh in the mid-eighteenth century.

从另一个组织坐标-时间——来观察特拉华河谷,可以区分出不同的建筑阶段。通过对装饰细节的关注,建筑历史学家可以将过去划分为一系列冗长而复杂的风格时期。大多数建筑完全不受”风格”序列的影响,或仅受其表面影响,因此,从建筑整体来看,只有三个主要阶段。第一个阶段在大西洋中部地区,从最初的定居时期一直持续到1760年左右,这是一个民族团结的建筑时期,保留了旧世界的各种形式和技术,并由此产生了土地上的多样性。第二个主要时间段包括最初接受新思想和新旧融合以创造新世界剧目的时期,其结果是土地上的地区同质化。地区文化在建筑实践中失去主导地位的时间点(尽管它并没有完全消亡,其表现形式仍然统治着环境)因地区而异。布伦斯基尔写道,1840年铁路的开通标志着英国地区性建筑的终结。美国东北部的情况似乎也是如此。在大西洋中部地区,地区性建筑的做法得到了更顽强的保留,直到第一次世界大战时代才被融入国家文化。在南部地区,这个时间还要更晚。在时间上,本文将重点关注第二个建设阶段的早期——广泛而深入的创新时期——18世纪第三季度;而在一个世纪后的更晚些时候,这一时期的遗产是特拉华河谷建筑的稳定模式,而时至今日仍是景观特征的模式则是18世纪中叶文化冲突和融合的产物。

It should be noted that most of the illustrations for this paper picture nineteenth-century expressions of eighteenth-century ideas. Late buildings, rather than structures that actually date to the eighteenth century, were chosen to illustrate the points in this paper for two reasons, both of them crucial to the paper’s intent. In the first place, basic house forms, because of the conservatism of builders and inhabitants, persisted unchanged despite the fluctuations of taste represented by architectural detail. Secondly, the major Mid-Atlantic house types of the eighteenth century continued to be erected for better than a century after their introduction or development, so that forms of eighteenth-century origin are not now rarities on the landscape. Buildings worth study are not difficult to locate, and contemporary fieldwork can teach much about eighteenth-century cultural patterns.

需要指出的是,本文的大部分插图都是十九世纪对十八世纪思想的表达。本文选择晚期建筑而非实际可追溯到十八世纪的建筑来说明本文的观点有两个原因,这两个原因对本文的写作意图都至关重要。首先,由于建造者和居民的保守性,尽管建筑细节所代表的品味有所变化,但基本的房屋形式却一直保持不变。其次,十八世纪大西洋中部的主要房屋类型在问世或发展一个多世纪后仍在继续建造,因此起源于十八世纪的房屋形式现在在风景中并不罕见。值得研究的建筑并不难找到,当代的实地考察也能为我们提供许多有关十八世纪文化模式的信息。

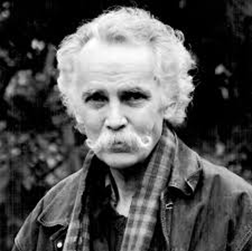

The earliest forms of human shelter in the valley changed with the insertion of the Georgian house type (Figure 11.1) into the awareness of builders in the middle of the eighteenth century. As a form it was a century old in England and on the Continent; as a geometric structure of geometric components, it was a Renaissance inspired notion of classical planning. The form, primly symmetrical, was employed in America as early as 1700 and was accepted for the home of affluent gentlemen the length of the Atlantic seaboard for the last three quarters of the eighteenth century, although its impact was not great until after the publication of handbooks advocating the Georgian style in the 1740s and 1750s. Like the drama of an earlier period, the Georgian form is an English interpretation of an Italian interpretation of Roman practice (with an optional half-step through Dutch interpreters). The Georgian form is usually considered an English contribution to American domestic architecture, but while that notion connotes accurately the acculturative situation, English Georgian was part of an international Renaissance style. Distinctively Scottish and Germanic expressions of the style were built in Pennsylvania, and the fact that the basic Georgian form was known in seventeenth-century central Europe facilitated its acceptance by Continental settlers in the Mid-Atlantic region. The definitive elements of the type rarely varied: externally, a low pitched roof (hipped on finer houses but usually gabled) and two openings per floor on the ends, five on the facade; internally, a double pile plan with two rooms on each side of a central hall containing the stair.

随着乔治亚式房屋在十八世纪中叶进入建造者的视野,山谷中最早的人类住所形式发生了变化(图11.1)。作为一种形式,它在英格兰和欧洲大陆已有一个世纪的历史;作为一种由几何构件组成的几何结构,它是文艺复兴时期受启发而产生的古典规划理念。早在1700年,美国就采用了这种通常情况下对称的形式,在十八世纪的后四分之三时间里,大西洋沿岸的富裕绅士们的住宅也采用了这种形式,不过直到18世纪40年代和50年代倡导乔治亚风格的手册出版后,这种形式才产生了巨大的影响。像早期的戏剧一样,乔治亚式风格是对罗马实践的意大利式诠释(也可以说一半是荷兰人的诠释)的英国式再诠释。乔治亚风格通常被认为是英国对美国家庭建筑的贡献,然而,虽然这一概念准确地包含了文化移入的情况,英国乔治亚风格是国际文艺复兴风格的一部分。这种风格在宾夕法尼亚州有着独特的苏格兰和日耳曼表现形式而乔治亚风格的基本形式在十七世纪的中欧已广为人知,这也为大西洋中部地区的大陆定居者接受这种风格提供了便利。这种风格的基本要素很少有变化:外部是低坡度屋顶(在较好的房屋中为坡度更高,但通常是低坡度),每层的两侧端部有两个开口,正面有五个开口;内部是双柱式平面,在包含楼梯的中央大厅两侧各有两个房间。

图11.1 乔治亚式房屋类型的主要转变: a.完整;b.三分之二;c.三分之一

The new idea was not radically different from older European folk practice. Medieval building was not wholly lacking in symmetry; bilateral symmetry was, in fact, an essential feature of western European folk design. The roof of the new type was shallow, but it was still a triangle that could be framed and covered in the old manner. A central passage, though hardly a formal hall was, as M. W. Barley points out in his excellent The English Farmhouse and Cottage, “a characteristic feature of the medieval house.” The idea of a symmetrical cover for a two room depth was alien to most old British building, but it was familiar enough to those who came in great numbers from central Europe. The Georgian form was new, but not too new, and backed by the taste makers of the period, it became firmly lodged in the Mid-Atlantic architectural repertoire. From the middle of the eighteenth century to the close of the nineteenth, the type was constructed as a stalwart farmhouse in stone, brick, log, or frame throughout the Mid-Atlantic region, achieving dominance at the region’s western end in the area of Somerset County, Pennsylvania, and standing as a very familiar form along the Delaware River and throughout New Jersey.

这种新理念与欧洲古老的民间做法并无本质区别。中世纪的建筑并非完全缺乏对称性;事实上,双边对称是西欧民间设计的一个基本特征。新式房屋的屋顶较浅,但它仍然是一个三角形,可以用旧式的方式加以围合和覆盖。正如巴利在其杰作《英国农舍和别墅》中所指出的那样:中央通道虽然算不上正式的大厅,但却是中世纪房屋的一个特征。对于大多数古老的英国建筑来说,两室进深的对称的屋顶是个陌生的概念,但那些大量涌入的中欧人对此已经足够熟悉。乔治亚时期的建筑形式虽然新颖,但还不算太新,在当时的品味定义者的支持下,它已牢牢地扎根于大西洋中部的建筑中。从十八世纪中叶到十九世纪未期,在整个中大西洋地区,这种类型的建筑都是用石头、砖、原木或框架建造的坚固农舍,在该地区西端宾夕法尼亚州萨默塞特郡地区占据主导地位,在特拉华河沿岸和整个新泽西州也是人们非常熟悉的建筑形式。

Being an idea, existing fully in the mind before its achievement as an object, the Georgian type was not only built of a variety of materials (form and technics being separate architectural subsystems), it was subject to formal modification. The most common transformation within the Georgian type consisted of a subtractive step yielding two-thirds of the complete idea, a house with two rooms on one side of the hall. Houses of the kind are seen occasionally as farmhouses through southern Pennsylvania and adjacent Delaware and Maryland. It is also the predominant, traditional town house type even beyond the region, being found commonly in cities such as Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Virginia, where Georgian house subtypes are unusual in the surrounding countryside. In New Jersey the two-thirds Georgian type is extremely common on the farm and in the village. Generally, it has a kitchen wing, lower and narrower than the bulk of the basic house, built off the gable along which the hall runs. An additional rural New Jersey Georgian modification amounts to a two thirds form in a single story expression. The occurrence of this house in central New Jersey is an example of the connections between New Jersey and Long Island, where the type is also found with frequency. On Long Island and in northeastern New Jersey, the chimney was often placed internally, New England fashion; in the part of New Jersey located within the Mid-Atlantic region, chimneys were built inside the gable end as they were nearly always in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

乔治亚式建筑是一种概念,在成为实物之前就已存在于人们的脑海中,它不仅由多种材料建成(形式和技术是独立的建筑子系统),而且还可以进行形式上的修改。在乔治亚式建筑中,最常见的改造方式是减法,即在大厅的一侧建造两个房间,从而产生了整体的三分之二的构思。在宾夕法尼亚州南部以及邻近的特拉华州和马里兰州,偶尔会看到这种房屋。在华盛顿特区和弗吉尼亚州的里士满等城市,乔治亚式房屋也是最主要的传统城镇房屋类型,甚至在该地区以外的地方也很常见。在新泽西州,三分之二乔治亚式住宅在农场和村庄中极为常见。一般来说,它有一个厨房翼楼,比基本房屋的主体更低更窄,建在大厅沿线的屋檐下。新泽西州农村乔治亚风格的另一种改良形式是单层三分之二的形式。这种房屋出现在新泽西州中部是新泽西州与长岛之间联系的一个例证,这种房屋在长岛也经常出现。在长岛和新泽西州东北部,烟囱通常建在内部,这是新英格兰的风格;而在新泽西州位于大西洋中部地区的部分,烟囱建在檐口内,这在宾夕法尼亚州和马里兰州几乎是常见的情况。

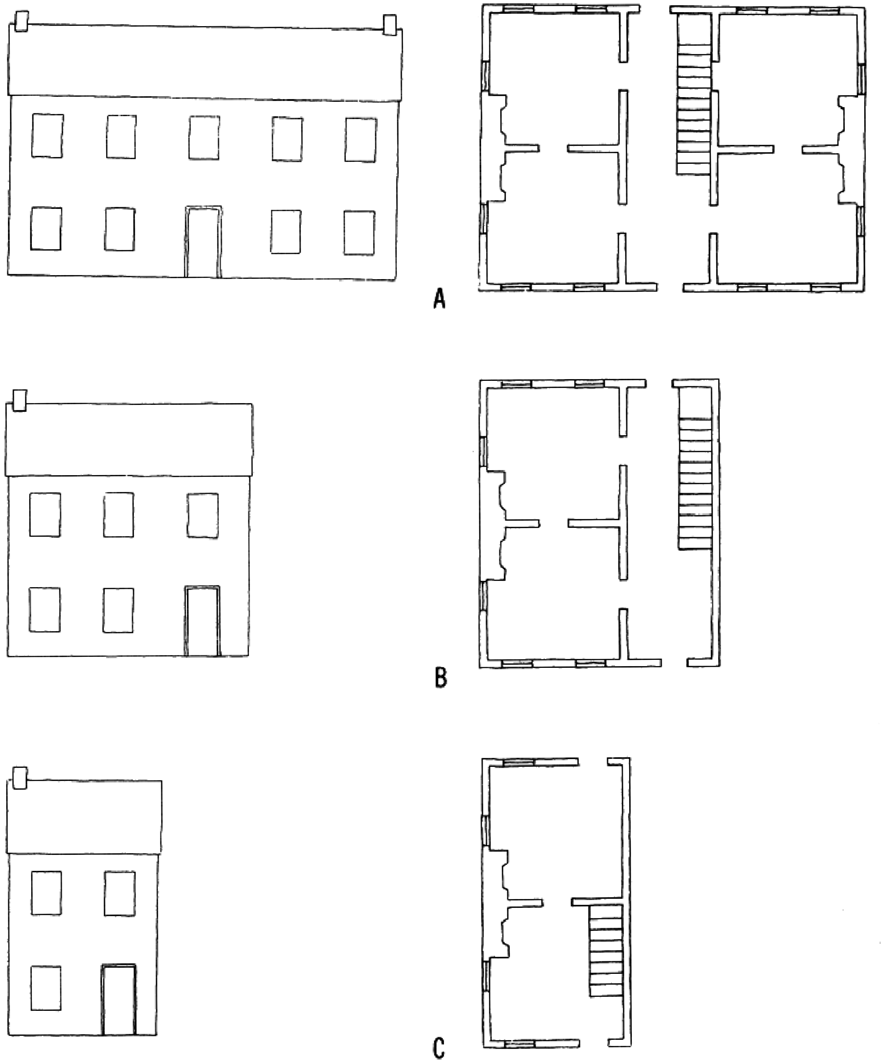

If the Georgian form could be reduced by one-third, it could be reduced by two-thirds, and the new form, one room wide and two deep, was a common town house in the Delaware Valley, as it was in London. Like larger town houses, it was often built as half a pair in the vicinity of the Delaware (Figure 11.2). In southeastern Pennsylvania, nearby Delaware, and particularly in the area of New Jersey just east of Philadelphia, it can be found, built of frame or log, brick or stone, as a farmhouse, generally with a wing off the non-chimney gable. The gable of this house, one-third of the Georgian type, is the same as that of houses that are two-thirds or all of the fundamental form, but the openings per floor on the facade are reduced from five to three to two (Figure 11.1).

如果说乔治亚风格的形式可以减少三分之一,那么它也可以减少三分之二,这种一室宽、两室进深的新形式是特拉华河流域常见的城镇住宅,就像在伦敦一样。与较大的城镇住宅一样,在特拉华河附近,这种住宅通常是半对式的。(图11.2)在宾夕法尼亚州东南部、特拉华州附近,特别是在费城以东的新泽西州地区,可以看到用框架或原木、砖或石头建造的农舍,一般在无烟囱的屋檐下有一个侧翼。这种房屋的檐口是乔治亚式的三分之一,与三分之二或完整基本形式的房屋的檐口相同,但立面每层的开口从五个减少到三个再到两个。

图11.2 这幅素描示意的是宾夕法尼亚州切斯特县西切斯特北达灵顿街200街区。由三分之一乔治亚式房屋类型组成的城市立面。这些建筑部分是砖石制部分是木制;部分是18世纪部分是19世纪建造——说明了乔治亚式风格房屋三分之一类型在立面上的多样性。

The transformations of the Georgian type tell a simple story. Ernest Allen Connally teaches the same lesson in his study of Cape Cod houses. People, being innovative, can modify ideas and fragment forms to suit economic and environmental needs. Houses that are portions of the entire idea were doubtless built by the same masters who built the full houses, though for people who had smaller families, less cash, or a smaller piece of land. The narrow, deep proportions of the one-third and two-thirds Georgian subtypes made them suited to small lots and crowded situations. The fact that when the architectural repertoire was rummaged

乔治亚式建筑的转变讲述了一个简单的故事。欧内斯特.艾伦.康纳利在研究科德角房屋时也讲了同样的道理: 人们具有创新精神,可以根据经济和环境的需要,改变想法和形式。仅有完整房屋一部分的房屋,无疑也是由建造完整房屋的屋主建造的,尽管他们的家庭规模较小、资金较少或土地面积较小。三分之一乔治亚式和三分之二乔治亚式亚的比例窄而深,适合小块土地和拥挤的环境。事实上,在寻找城镇房屋类型时,人们选择了部分乔治亚式子类型作为适合环境的形式,这揭示了大西洋中部城镇规划中的传统乡村元素。如果建造者是根据问题而不是根据有限的民间构件进行设计,那么他很可能会建造一座薄型房屋,其屋檐朝向街道,就像欧洲古镇的图片或 19 世纪晚期宾夕法尼亚州工厂和矿业公司城镇中的房屋一样。但是,规划师的作品是乡村风格的,尽管这意味着椽子必须有很长的跨度,但他还是希望他在城里的房子拥有像在乡村一样有结构和位置。在房子后面,他有一块花园地和一个小谷仓,这样,小镇就由一排排微型农场组成,房子则是乡村风格,长边,或声称是长边的长边,朝向道路。我们的创新者是一个保守的人:他将创新限制在传统的结构中(入口、屋脊线和道路之间的关系)中,以此来安慰自己,他将创新限制在简单的加减法上——加法是因为部分形式可以在建成后扩大,以产生完整的形式,而完整的形式可以再扩大三分之一或三分之二。

The little family of house types on the Georgian plan is a major characteristic of the Mid-Atlantic region. In neither of the adjacent coastal regions, North or South, did the Georgian set of ideas become as deeply embedded in the thinking of traditional builders. The existence of the Georgian type did more than inspire novel forms that collectively signal a new, impurely folk phase in architectural chronology. The basic form was dissected, and some of its components were fused with elements from pre-Georgian building to produce, in a flurry of eighteenth-century innovation, two new house types, both of which showed much more creative thought than occasional refinements within the Georgian form and style such as Cliveden in Germantown or Mount Pleasant in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park.

乔治亚式平面图上的几种房屋类型是大西洋中部地区的一大特色。在邻近的沿海地区,无论是北部还是南部,乔治亚风格的一系列理念都没有像这样深入传统建造者的思想。乔治亚风格的存在不仅激发了新的形式,还共同标志着建筑编年史上一个新的、不纯粹的民间阶段。在十八世纪的创新浪潮中,人们对乔治亚式建筑的基本形式进行了剖析,并将其中的一些元素与前乔治亚式建筑的元素融合在一起,从而产生了两种新的房屋类型,这两种类型都比乔治亚式建筑形式和风格中偶尔出现的改进(如日耳曼镇的克莱文登或费城费尔蒙公园的悦山)更能体现出创造性的思想。

In the German areas of the region, including spots in West Jersey as well as the more predictable broadening arc in Pennsylvania from Northampton to York counties, an off-center chimney characterizes a common house type, built regularly up to about 1770. Rendered, generally, in stone or log, it exists in one and two story examples. Typically, it has a three room plan; an offset door opens into a long, narrow kitchen incorporating the house’s deep fireplace. Behind the chimney, a broader front room serves as a parlor, a smaller back room as the chamber (Figure 11.3). The size of the house cues internal modifications, such as partitioning the kitchen of a large house or eliminating the wall between bedroom and parlor in a small house. The plan is like that of peasant dwellings in Switzerland and the Rhine Valley. Its depth and and proportions,

在该地区的德裔地区,包括西新泽西州的一些地方,以及宾夕法尼亚州从北安普顿郡到约克郡的弧线较宽的地区,偏离中心的烟囱是一种常见的房屋类型,在 1770年之前一直有规律地建造。烟囱一般用石头或原木砌成,有单层和双层两种。这种房屋通常有三个房间,偏门通向一个狭长的厨房,厨房内有一个很深的壁炉。烟囱后面是一个较宽的前厅,用作会客厅,后面是一个较小的后厅,用作卧室。(图11.3)房屋的大小决定了内部的改动,比如在大房子里隔开厨房,或者在小房子里取消卧室和客厅之间的墙。这种规划与瑞士和莱茵河谷的农民住宅如出一辙。作为中世纪晚期欧洲大陆的产物,它的进深和比例与乔治亚式风格的想法并不完全相悖;它的平面图与三分之二的乔治亚式风格房屋子类型并不完全不同。这种相似性无疑有助于人们接受新的乔治亚式风格,并促进了新旧两种风格的融合,使其成为从宾夕法尼亚州伯利恒到马里兰州弗雷德里克的大西洋中部中心地带最常见的类型。普通房屋的平顶和外部准对称性使学者们误以为其起源于英格兰和新古典主义。但这一外壳掩盖了古老大陆式的内部。这种房屋的檐口是严格的乔治亚式风格,但其正面有四个而不是五个开口,以适应内部三室的布局。一扇门仍然将访客带入狭长的房间,但通常(但不总是)还有另一扇前门通向客厅。这第二扇门很少使用,通常没有纱门,而且有各种有趣的解释,似乎是为了对称布置,但由于旧厨房比客厅窄,仔细观察窗户间距就会发现,外墙上的对称往往是假的。中央的大烟囱已被屋檐上的烟囱取代。如果不仔细观察,在路上隆隆驶过的人可能会以为自己看到了最新的样式——拥有正式大厅的乔治亚式风格房屋;这是建筑者希望传达的印象,而他的妻子则在屋内以老式的方式工作,对她的后代说德语。宾夕法尼亚州的农舍是十八世纪的妥协产物,到了二十世纪,这些农舍由原木、石头、砖块或框架建造而成,屋面铺有耐候板,耐候板下部则铺有砖块。与特拉华河周边的其他类型房屋一样,这些房屋也经常涂上灰泥。

图11.3 宾夕法尼亚州乡村房屋类型发展的示意图:A.欧陆式中央烟囱房屋类型;B.宾西法尼亚式房屋类型——欧陆式中央烟囱房屋类型经过改造以适应乔治亚式美学。右边的烟囱充当炉子,为客厅供暖。

This synthetic type is the result of the same kind of mental activity that generated the common New England house type, which packaged the old English saltbox house in a symmetrical container. In both houses, Old World interiors were externally disguised to be acceptable. Both house forms teach us that the skins of houses are shallow things that people are willing to change, but people are most conservative about the spaces they must utilize and in which they must exist. Build the walls of anything, deck them out with anything, but do not change the arrangement of the rooms or their proportions. In those volumes—bounded by surfaces from which a person’s senses rebound to him—his psyche develops; disrupt them and you can disrupt him.

这种综合的类型是产生新英格兰常见房屋类型的同一种心理活动的结果,它将古老的英国盐箱房屋包装在一个对称的外壳中。在这两种房屋中,旧世界的内部装饰都是经过外部伪装后才被接受的。这两种房屋形式都告诉我们,房屋的表皮是人们愿意改变的浅层事物,但人们对房屋必须利用的空间和房屋必须存在的空间却最为保守。你可以用任何东西砌墙,用任何东西装饰,但不要改变房间的布局和比例。在这些空间中,人的感官体验会从空间表面反映到他身上,他的心理也会在这些表面中得到发展;打破这些空间你就会破坏他。

The kind of house that preceded the Georgian type as predominant in the intensely English sections around Philadelphia and across the river in New Jersey was as venerable a folk form as the Germanic three room house. It has been named, by Kniffen, the I house (its tall, thin gable might be envisioned as an upper case I). Its definitive characteristics are two story height, one room depth, and length of two or more rooms. Known across England at the time of initial settlement in the New World, it was commonly built in all the English colonies north of the middle of the North Carolina coast during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The early form, in most instances, consisted of two rooms on the ground floor, one of which was square, called a hall, and used for most living; it was often a bit longer than the other room, the parlor. In New England, logically enough, the East Anglian central chimney form was most usual; in the Chesapeake Bay area, west British external chimneys were most characteristic. In the Mid-Atlantic area, the chimneys were built flush within each gable wall.

The introduction of the Georgian form into I house country engendered the same results in the Chesapeake and Mid-Atlantic areas. The I house retained its one room depth (without which an example would be classified as a different type), but its new plan approximated the front half of the Georgian house with rooms of about equal size separated by a hall. The five opening facade became standard, so that from the front a Georgian house and a Georgian-influenced I house are indistinguishable. The gable view, however, is quite different. The gables of early I houses were normally blank, though an off-center window per floor became common on later Pennsylvania houses. Particularly throughout southern New Jersey and the Maryland Eastern Shore, there are often two windows on each floor, disguising the old I house even more completely as a Georgian house.

在切萨皮克和大西洋中部地区,乔治亚式房屋形式被引入“I”型房屋后也产生了同样的结果。“I”型房屋保留了一个房间的进深(如果没有这个进深,就会被归类为另一种类型),但其新的平面布局接近于乔治亚式房屋的前半部分,房间大小基本相同,中间由一个大厅隔开。五开间的外立面成为标准,因此从正面看,乔治亚风格的房屋和受乔治亚风格影响的“I”型房屋是无法区分的。然而,从屋檐的角度看却截然不同。早期“I”型房屋的屋檐通常是空白的,但在后来的宾夕法尼亚州房屋中,每层偏离中心的窗户变得很常见。特别是在新泽西州南部和马里兰州东海岸,每层通常都有两扇窗户,这就更彻底地将老式“I”型房屋伪装成了乔治亚式房屋。

Most extant Mid-Atlantic I houses are frame, though some in the Alleghenies, on the region’s western frontier, are log. In Bucks and Chester counties particularly they are of stone. They were frequently built of brick, most notably in southern New Jersey, and in Salem and Cumberland counties where glazed headers were worked into elaborate diamond and zigzag patterns and into dates and initials—a mode of decoration that was quite common in Tudor England and occasional along the southern Atlantic coast.

大多数现存的中大西洋一号房屋都是框架结构,但在该地区西部边境的阿勒格尼山脉,有些房屋是原木结构。特别是在巴克斯郡和切斯特郡,这些房屋都是石头砌成的。这些房屋通常由砖砌成,最明显的是在新泽西州南部,以及塞勒姆和坎伯兰郡,这些地方的釉面砖头被加工成精致的萎形和人字形图案,以及日期和首字母——这种装饰方式在都铎时期的英格兰非常常见,在大西洋沿岸南部也时有发生。

The I house concept, expressed like all basic concepts in diverse materials, underwent expansion through various kinds of shed and ell additions to the rear—if not actual additions, these are still conceptual additions like suffixes on words. Also, a two story room—square in good English fashion, like the house’s main rooms— was occasionally added onto one gable, producing a double parlor house, a form that, owing to its popularity in England, one would expect to have been more usual in America. Like the Georgian house, the I house could be split, and houses that are two-thirds of the full form, one room and a hall, are found in Pennsylvania villages and in the countryside of southwestern New Jersey and eastern Delaware. Once introduced, the Georgian form was worked upon in many ways: it was built unaltered of a variety of materials: it was reduced and enlarged systematically to fit spatial or economic requirements; and it was broken down so that some of its components could be combined with components from pre-Georgian architectural repertoires, both British and Germanic, to produce new house types.

像所有基本概念一样,“I”形房屋的概念也是用不同的材料表现出来的,它通过在后部加建各种棚屋和椭圆形房屋而得到扩展-即使不是实际的加建,也是概念上的加盖,就像词的后缀一样。此外,偶尔也会在一个屋檐上加盖一个两层楼的房间——就像房子的主房间一样,是英式风格的方形-从而形成了双会客厅式的房子,由于这种形式在英国很受欢迎,人们会认为它在美国更常见。与乔治亚式房屋一样,“I”型房屋也可以拆分,宾夕法尼亚州的村庄以及新泽西州西南部和特拉华州东部的乡村都有这种房屋,它是完整形式的三分之二,即一个房间和一个大厅。乔治亚风格一经引入,便以多种方式加以发展:它被原封不动地使用各种材料建造;它被有计划地缩减和扩大,以适应空间或经济上的需求;它被拆解,从而使其某些组成部分可以与乔治亚风式格之前的英国和日耳曼建筑中的组成部分结合起来,形成新的房屋类型。

Culture is an inventory of learned concepts. The cultural process consists of selecting from among the concepts, some of them new, some of them old, when a problem such as walking, courting, or building a barn has to be solved. Some concepts are fully accepted, some are modified, some are torn apart and combined with others, and some are rejected. The acceptance of the Georgian form meant not only the appearance of new things but also the disappearance of old things. Some old ideas were specifically incompatible: if the Georgian ideal of chimneys poking up at either gable were embraced, the central fireplace of the three room Continental house could not remain, despite the elaborate flues constructed to that end in at least one house. Some ideas were lost as a part of the general but rapid move during the third quarter of the eighteenth century toward a prosperous homogeneity—a move facilitated by a new and prestigious architectural concept, offered at once to all people, and to all somewhat foreign, somewhat familiar. A few manifestations of the ethnically distinct architectural ideas of the early period in Mid-Atlantic building can still be found to give the fieldworker an impression of the early heterogeneity—of the ideas that were rejected. Among the lost forms was the Swiss bank house, although its multi-level concept may have survived in the semisubterranean cooking cellars of many Mid-Atlantic farmhouses. The low, stone Scotch-Irish cabin was also lost as New World Ulstermen moved into larger, more fashionable dwellings. Although translated into log or frame, the little northern Irish cabin did persist with tenacity on the Appalachian frontier. Apparently never of much importance, Scandinavian log construction, too, was lost during this period when an acceptable but limited folk architectural repertoire was built up in the New World out of Old World stuff. By mid-century Scandinavian log construction had been completely overwhelmed by the totally different kind of log construction usual in America, which was introduced from central Europe.

文化是一个关于习得概念的详目。当需要解决行走、求爱或建造谷仓等问题时,文化过程就是从这些概念中进行选择,其中有些是新概念,有些是旧概念。一些概念被完全接受,一些被修改,一些被拆解并与其它概念相结合,还有一些则被摒弃。接受乔治亚式风格不仅意味着新事物的出现,也意味着旧事物的消失。有些旧观念是特别不相容的:如果接受了乔治亚式风格的烟囱在两边屋檐上竖起的想法,那么欧陆式三室房屋的中央壁炉就无法保留,尽管肯定有房屋为此建造了精致的烟道。在十八世纪第三季度,人们普遍而迅速地向繁荣的同质化迈进,一些观念也随之消失,而一种全新的、享有盛名的建筑理念则为这种迈进提供了便利,它同时摆在所有人面前,让所有人感到有些陌生,又有些熟悉。在大西洋中部的建筑中,仍然可以找到一些早期不同种族建筑理念的表现形式,让实地考察者感受到早期的异质性,以及被摒弃的理念。消失的建筑形式包括瑞士斜坡房屋,尽管其多层概念可能在许多大西洋中部农舍的半地下灶窖中得以保留。随着新世界的阿尔斯特人搬入更大、更时尚的住宅,苏格兰-爱尔兰式的低矮石屋也随之消失。尽管被改建成原木或框架结构,爱尔兰北部的小木屋确实在阿巴拉契亚边疆顽强地存在着。斯堪的纳维亚原木建筑显然并不重要,但也在这一时期消失了,因为新世界用旧大陆的材料建造起的民间建筑能被接受但数量有限。到本世纪中叶,斯堪的纳维亚原木建筑已完全被从中欧引进的美国常见的一种完全不同的原木建筑所取代。

The houses and other folk buildings that typify the Mid-Atlantic landscape—the bams and mills, meeting houses and corncribs—can be explained as artifacts largely by reference within the architectural system. Unlike a utopian designer, the folk planner employs an old and established form, despite changes of use and environment. In arranging a complete form in a spatial relationship to other forms, the folk planner f inds himself with an abundance of problems. The lay of the land, the ranges of wind, rain, and temperature, the changes in the social and economic systems—all make adherence to a type, a traditional template for correctness, more difficult in the construction of composite, noncontinuous forms, such as towns or farms, than it is in the construction of unitary, continuous forms, such as houses or bridges. Exactly the same house type might work nicely in a metropolis or a wilderness, but different settings obviously require quite different relationships between the house and other structures.

作为大西洋中部景观典型代表的房屋和其他民间建筑——碾坊和磨坊、集会所和玉米仓——在很大程度上可以通过建筑体系中的参照物来解释为物件。与乌托邦式的设计师不同,尽管用途和环境千变万化,但民间设计师采用的是古老而固定的形式。在安排一个完整的形式与其他形式的空间上的关系时,民间规划师发现自己面临着大量的问题。地形、风力、雨量和温度的变化、社会和经济制度的变化,所有这些都使得在建造城镇或农场等复合型、非连续性建筑时,比建造房屋或桥梁等单一型、连续性建筑时更难遵循一种类型,一种传统的正确性的模板。完全相同的房屋类型可能在大都市或荒野中都很适用,但在不同的环境中,房屋与其他结构之间的关系显然需要有很大的不同。

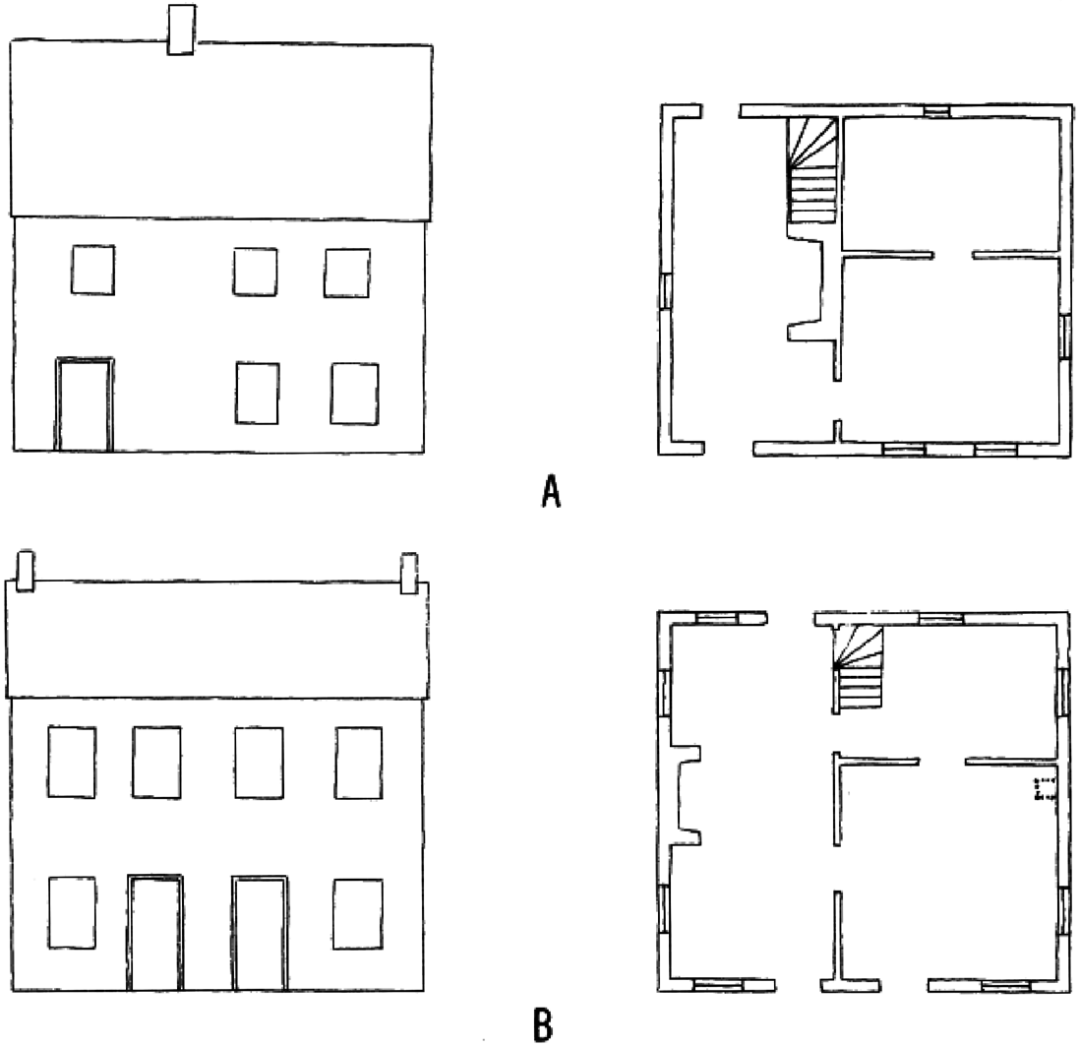

Two distinct, fundamental farm plans exist in the Delaware Valley; in their ideal forms they stay pretty obediently on opposite sides of the river, though both tend to lose the rigor of their pattern at the Delaware and especially on the Jersey bank above Philadelphia. In southern New Jersey, the ideal from which reality varies is a hollow square. It consists of a house, an I house or some Georgian subtype, generally, facing the road with the barn, almost always a three bay, side-opening barn of one level, such as was most common in England, directly behind it or set a bit to one side. In some cases the ridge lines of house and barn are set at right angles though a parallel arrangement is more common and seems to have been the ideal. On one side a line of buildings, consisting mainly of a long shed open on the inside, connects the spheres of house and barn. A few other dependencies are placed opposite this line forming a courtyard, a hollow rectangle—house at the front, barn at the rear, with one boundary typically a little ragged. As one moves northward through New Jersey, this tight plan loosens up. Some farms exhibit the major structural elements, the parallel relation of house and barn, but they lack the sheds enclosing the square. In others the barn and sheds from a courtyard of sorts—what would be called a “fold-yard” in England—but the house is not a part of the rectangular layout. This situation is common in the North and suggests that such farms may be products more of Northern than of Mid-Atlantic thinking.

特拉华河谷地区有两种截然不同的基本农庄规划;在理想状态下,它们顺从地保持在河对岸,但在特拉华河畔,尤其是费城上方的泽西河岸,这两种规划往往会失去其严谨的模式。在新泽西州南部,与现实不同的理想形态是一个中空的正方形庭院。它由一栋房屋组成,一般是“I”型房屋或乔治亚式子类型房屋,与几乎都是三间的谷仓一起,朝向道路、侧开的单层谷仓,如在英格兰最常见的谷仓,直接位于房屋后面或稍稍偏向一侧。在某些情况下,房屋和谷仓的脊线成直角,但平行排列更为常见,而且似乎是理想的排列方式。在房屋和谷仓之间的一侧有一排建筑,主要由一个内侧敞开的长棚子组成。在这条线的对面还有一些其他的附属建筑,形成一个庭院,一个中空的矩形——房屋在前,谷仓在后,边界通常有点粗糙。向北穿过新泽西州后,这种紧凑的规划逐渐松下来。一些农场展现出了主要的结构元素,即房屋和谷仓的平行关系,但它们缺少包围广场的棚屋。在另一些农场中,谷仓和棚屋组成了一个庭院——在英国被称为”折叠式庭院”,但房屋并不是矩形布局的一部分。这种情况在北方很常见,说明这类农场可能更多是北方而非大西洋中部思想的产物。

When the house is rarely an I house and the barn is usually a Yankee style basement barn, the fieldworker is likely to be near the Kittatinny Mountains, and his suspicion that he is leaving the Mid-Atlantic region is confirmed. In this hilly section of western New Jersey, farms on which there is no clear statement of the square are common; there is instead the simple clustering of some outbuildings around the barn and others around the house with a psychological separation between the two areas. The groups of buildings may be considered, respectively, as extensions of house or barn and the two areas as spheres of sexual control, the barn being the man’s domain, the house, the woman’s. While it takes different forms in different subregions, this loose dual arrangement appears to be an Americanism with multiple origins, lacking sufficient precision to enable the scholar to make confident assertions about Old World provenance. The hollow square, which predominates in flat southern New Jersey but breaks up in the stony hills of the upper Delaware Valley, is an English form. Probably related to similar plans in northern Europe, the hollow square, including or omitting the house, dates to Saxon times in England, where it is still regularly found, and in Ireland it is restricted to the English-planted areas. In America, derivative plans are found not only in New Jersey but also on Long Island and in upstate New York. The farms of New England occasionally consist of a house and barn in a parallel arrangement, though the two are joined by a service wing; the similarities are suggestive of a possible genetic relationship in old England between these two tight farm plans, which are outstanding in a country characterized by loose farm planning.

当房屋很少是“I”型房屋,而谷仓通常是洋基风格的地下室谷仓时,田野调查员很可能就在基塔廷尼山脉附近,他对自己正在离开大西洋中部地区的猜测得到了证实。在新泽西州西部的这片丘陵地带,没有明确方形庭院的农场很常见;相反,谷仓周围有一些简单的附属建筑群,房屋周围也有一些附属建筑群,两个区域在心理上是分开的。这些建筑群可分别视为房屋或谷仓的延伸,而这两个区域则被视为是两性控制的范围,谷仓是男人的领地,而房屋则是女人的领地。虽然在不同的子地区有不同的形式,但这种松散的双重安排似乎是一种美国式的多重起源,缺乏足够的精确性,使学者无法对旧世界的来源或新世界的古代性做出自信的断言。空心方形主要出现在新泽西州南部的平原地区,但在特拉华河谷上游的石质丘陵地带则被打破,这是一种英国形式。空心方形(包括或不包括房屋)可能与北欧的类似规划有关,在英国可以追溯到撒克逊时代,在那里仍经常可以看到,在爱尔兰则仅限于英国人种植的地区。在美国,衍生出的规划不仅出现在新泽西州,也出现在长岛和纽约州北部。新英格兰的农场偶尔也会由房屋和谷仓并列组成,但两者之间有一个厢房连接;这些相似之处表明,在以农场布局松散为特点的国家,这两种紧凑的农场布局在旧英格兰可能存在遗传关系。

The ideal in southern Pennsylvania and its areas of cultural continuity, west central New Jersey, central Maryland, and the northern Valley of Virginia, consists of lining up the house and barn gable to gable and positioning this linear structure so that the fronts of both the house and the barn face south, east, or somewhere in between. The front of the house is obvious, but the barn’s front, in traditional terms, is the side with the doors into the stables—the side on which the manure, a sign of agricultural success, is displayed in early spring—and not necessarily the side into which one would drive a wagon or truck. Many different kinds of houses and barns were plugged into the slots in this linear structure. Around the southern and western borders of the Mid-Atlantic region, in Maryland and Virginia particularly, the house slot was usually filled with an I house. Through the center of the region the house was generally a Georgian or Germanic farmhouse, and one often sees modern bungalows neatly inserted in the dwelling’s traditional position on the farm. In hilly areas of rocks and subsistence farming, eastern Northampton, northern Chester and York, and Bedford counties, Pennsylvania, especially, the barn is often one level. Through most of the western subregion of the Mid-Atlantic area, the barn slot in the farm structure is filled with some variety of bank barn. Prefab and cement block barns, even those lacking any formal connection with the old tradition, still tend to be related traditionally to the rest of the farm’s buildings.

在宾夕法尼亚州南部及其文化延续地区、新泽西州中西部、马里兰州中部和弗吉尼亚州北部山谷理想的做法是将房屋和谷仓的屋檐排成一排,并将这种线性结构定位,使房屋和谷仓的朝南朝东或介于两者之间。房屋的正面是显而易见的,但谷仓的正面,按照传统的说法,是有通往马厩的门的一面,也就是在早春时节堆放粪便的一面,粪便是农业成功的标志,而不一定是马车或卡车驶入的一面。许多不同类型的房屋和谷仓都被塞进了这种线性结构的空隙中。在大西洋中部地区的南部和西部边界,特别是马里兰州和弗吉尼亚州,房屋的空隙通常被填入“I”字型房屋。在该地区的中部,房屋一般是乔治亚式或日耳曼式的农舍,人们经常可以看到现代平房整齐地排列在农舍的传统位置上。在宾夕法尼亚州北安普顿东部、切斯特和约克郡北部以及贝德福德郡等岩石和自给农耕的丘陵地区,谷仓通常是单层的。在大西洋中部地区的大部分西部子地区,农场结构中的谷仓的空隙都是由各种斜坡谷仓填充的。预制谷仓和水泥砌块谷仓,即使是那些与旧传统缺乏任何正式联系的谷仓,仍倾向于与农场的其他建筑保持传统联系。

As long as the barn was one level, the problems involved in the achievement of the ideal layout were not hard to conquer. With the development of the bank barn, the planning problem became complicated. T he bank barn developed at about the same time as the pair of syncretistic Mid-Atlantic house types, and it was, like them, a product both of the fragmentation of preexisting forms and of the reordering and meshing of their elements. It seems to be an application of the multi-level, banked concept, common on barns in northwestern England and on barn and house combinations in north central Switzerland and the Black Forest, to the single level double-crib barn of Swiss ancestry. The bank barn of the Mid-Atlantic is typified by a cantilevered forebay over the stabling doors at the front and a ramp leading to its upper level at the rear. The problems involved in planning a farm that included a bank barn were not solely the linear arrangement and southerly exposure but also the location of a grade into which the barn could be built. Despite the complexity of the requirements, the ideal generally materialized on the land although topography occasionally caused compromise. In some areas houses were not traditionally backed into a bank, so that the barn was constructed slightly uphill of the house, crooking the plan. Generally, the house and the barn were positioned squarely to the rise of the land, like English bank barns, which seem to have provided part of the suggestion for the Pennsylvania barn, so that a curved piece of terrain caused the buildings to be related along the contour, bending the plan. In these ways topography served to distort the ideal.

只要谷仓是单层的,实现理想布局所涉及的问题就不难解决。随着斜坡谷仓的发展,规划问题变得复杂起来。斜坡谷仓与这对大西洋中部混合型房屋差不多是在同一时期发展起来的,与它们一样,斜坡谷仓既是对原有形式进行分割的产物,也是对其元素进行重新排序和组合的产物。它似乎是将英格兰西北部谷仓以及瑞士中北部和黑森林谷仓和房屋组合中常见的多层、斜坡式概念应用到了瑞士祖先的单层双面谷仓。中大西洋地区的斜坡谷仓的典型特征是,前面的牲口棚门上有一个悬臂式前廊,后面有一个斜坡通向上层。规划一个包括斜坡谷仓的农场所涉及的问题不仅仅是线性布置和朝南的朝向,还有谷仓可以建造的地势位置。尽管需求很复杂,但理想一般都能在土地上实现,尽管地形偶尔会需要妥协。在某些地区,房屋并不是传统意义上的背靠河岸,因此谷仓建在房屋的稍上坡处,使平面图出现偏差。宾夕法尼亚谷仓的部分设计灵感来源于英国的银行谷仓“,这种谷仓与地势的高低相适应,因此一块弯曲的地形会使建筑沿着等高线分布,从而使平面图发生弯曲。通过这些方式,地形改变了理想模式。

When it became fashionable to have the house front on the road, an additional factor of confusion was introduced. If the road ran east-west and the farm were on the north side of the road, no trouble arose. If the farm were on the road’s south side, a choice had to be made. Some farm planners ignored the road, situating the house with its back turned to it, leaving the house and barn in alignment facing the early sun. Others compromised by placing the front of the house and the back of the barn to the road; in this way, the aesthetic arrangement of ridge lines was retained, though the practical tradition of the dwelling’s orientation was lost. A road running in an inconvenient direction, northwesterly say, presented even greater problems. Many ignored the road, letting it run through or by the farm without influencing the organization of the buildings, so that an appropriate slope for the barn and the cardinal points were the only factors considered in the accomplishment of the ideal. Others built the house on the road, even if it meant that the house faced into the coldest winds. The barn could have been placed in alignment, preserving the aesthetic tradition while violating the practical tradition; however, the barn was left so that the morning sun bathed the barnyard, and the farm’s plan became L-shaped—a compromise that is frequently seen. When neither hillside nor road allowed the expression of the ideal, disruption of both the practical and aesthetic—economic and artistic—traditions resulted. But the first step in planning was site selection, and such sites were usually avoided; farms lacking any suggestion of linear organization and southern orientation are rare.

当把房屋正面朝向道路成为一种时尚时,又多了一个造成混乱的因素。如果道路是东西走向,而农场在道路的北侧,就不会出现问题。如果农场在路的南侧,就必须做出选择。一些农场规划者无视道路,将房屋背对着道路,让房屋和谷仓朝向太阳。另一些人则做出妥协,将房屋的正面和谷仓的背面朝向道路;这样一来,虽然保留了屋脊线的美学布局,但却失去了住宅朝向的实用传统。西北方向的道路很不方便,这就带来了更大的问题。许多人忽视了道路,让它穿过或经过农场,而不影响建筑物的布局,因此,谷仓的适当坡度和基本要点是实现理想的唯一考虑因素。其他人则把房子建在路上,即使这意味着房子要迎着最寒冷的风。谷仓可以对齐,这样保留了美学传统,但违反了实用传统;然而,谷仓被留了下来,这样清晨的阳光就能沐浴在畜栏上,农场的规划也变成了L形——这是经常看到的折中方案。当山坡和道路都不允许表达理想时,实用和审美——经济和艺术——传统就会被破坏。但规划的第一步是选址,而这种选址通常是要避免的;缺乏任何线性组织和南向朝向的农场非常罕见。

The forces that affect change in the cultural process are easily ordered in an examination of the problems solved in structuring a farm’s components. Given an ideal, there are aesthetic forces for its continuation (the familiarity of the linear or the rectangular plans) and aesthetic forces for its disruption (the desire to orient the house to the road). There are practical forces for its continuation (the warmth of the southerly aspect, the utility of the courtyard arrangement) and practical forces for its disruption (the need for a slope in Pennsylvania, the need for flat land in New Jersey).

在研究农场各组成部分的结构所解决的问题时,很容易对影响文化进程变化的各种力量进行排序。如果有一个理想,就会有美学的力量促使其延续(对线形或矩形规划的熟悉感),也会有美学的力量促使其中断(希望房屋朝向道路)。有延续理想的现实力量(南向的温暖、庭院布置的实用),也有破坏理想的现实力量(宾夕法尼亚州需要斜坡,新泽西州需要平地)。

The two ideal farm layouts of the Delaware Valley act as modulations between European and American farm patterns. In both, unlike the plans found throughout most of the United States, the house and barn were considered as parts of a single, formal unit rather than as separate foci for units related only by extra architectural systems. The separation one senses between the house and barn in the Midwest, or indeed in southwestern Pennsylvania or northwestern New Jersey, is not present in the older Delaware Valley farms. Still, in general, the Delaware Valley farm plans, as sets of spaces set aside for particular uses, were not as tight or integrated as farm-plans in the Old World.

特拉华河谷的两种理想农场布局是欧洲和美国农场模式之间的调和。与美国大部分地区的规划不同,在这两种规划中,房屋和谷仓被视为一个单一的正式单元的组成部分,而不是仅由建筑外系统联系的单元的独立中心。在中西部,或者宾夕法尼亚州西南部或新泽西州西北部,人们感觉到的房屋和谷仓之间的分离在特拉华河谷的老式农场中并不存在。不过,总的来说,特拉华河谷的农场规划,作为为特定用途预留的空间,并不像旧世界的农场规划那样紧凑或完整。

The origin of the linear plan may lie in buildings or ranges of buildings that housed the farmer at one end and his stock at the other. These are found in many of the parts of the Old World from which the Mid Atlantic settlers came: in England, Wales, Ireland, Scotland, Switzerland, and the Rhine Valley. Germans in nineteenth-century Wisconsin erected buildings housing both people and stock, and there are reports by a traveler and two tax assessors of similar buildings in Pennsylvania. The first house built by the Moravians at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was a twenty-by-forty log building that housed people at one end and animals at the other. But clearly the pattern was never usual. Arriving in the New World with the tradition of a combined house and barn, the farm planner seems to have exploded the old building. The building’s components were individually unaltered, and they were ordered linearly, but he let daylight in between them.

线性规划的起源可能在于一端为农民、另一端为牲畜居住的建筑或建筑群。这在旧世界的许多地区被发现,中大西洋的移民正是来自这里,如英格兰、威尔士、爱尔兰、苏格兰、瑞士和莱茵河流域。十九世纪威斯康星州的德国人建造了既能住人又能住牲畜的建筑,一位旅行者和两位评税员也报告了宾夕法尼亚州类似建筑的情况。摩拉维亚人在宾夕法尼亚州伯利恒建造的第一座房屋是一座 20×40 的原木建筑,一端住人,另一端住牲畜。但很明显,这种模式从来都不常见。来到新世界后,农场规划者似乎打破了房屋与谷仓相结合的传统,将旧建筑改头换面。建筑的各个组成部分都没有改变,它们呈线性排列,但他在它们之间留出了空隙。

The activities on the farm were spread out and separately housed; the holdings that were loosely bound into the agricultural community were similarly scattered. In Britain before and during the Roman presence, farms were independently possessed and isolated. This ancient European pattern survived through the Middle Ages only in those mountainous areas of the Continent and the British Isles that were relatively undisturbed by the waves of violence called history. In the most densely settled sections, where the land had many stomachs to support and was worth fighting over, the agricultural village with its clustered habitations, outfield system, and cooperative style became the norm. But the old, individualistic sense of status dependent upon the accumulation of territory and chattels was not wholly lost in the medieval, communal setting; and although tight agricultural villages were planned in Spanish, French, and English America, the settlers of those villages scattered rapidly and greedily into the countryside, claiming and working isolated holdings,68 with exceptions only in extremely authoritarian situations such as those that existed in early New England and Mormon Utah. With antecedents in the land-use patterns of the Scotch-Irish and with support from the land allotment schemes of William Penn, the separate, single-family farm became the usual pattern for the Mid-Atlantic and for the United States.

农场上的活动分散开来,各自为政;松散地结合在农业社区中的土地也同样分散。在罗马人统治之前和统治期间的英国,农场都是独立拥有的,并且与外界隔绝。这种古老的欧洲模式一直延续到中世纪,只存在于欧洲大陆和不列颠群岛相对较小的山区。在人口最稠密的地区,土地养活了许多人,值得为之争斗,因此农业村落及其聚居地、外场系统和合作风格成为常态。但是,在中世纪的社区环境中,依赖于领土和动产积累的古老的个人主义地位意识并没有完全消失。虽然西班牙、法国和英国在美洲规划了严密的农业村落,但这些村落的定居者迅速而贪婪地分散到农村,要求并耕种孤立的土地,只有在极端专制的情况下才例外,如早期的新英格兰和摩门犹他州。由于苏格兰-爱尔兰人的土地使用模式以及威廉.潘恩的土地分配计划的支持,独立的单户农场成为中大西洋地区和美国的惯常模式。

The availability of land is the most obvious among the factors that made up the New World environment and that functioned causally to encourage an abrupt change in planning. The Delaware Valley settler’s holding was much larger than his European father’s; he could spread his buildings and farms around; more significantly, he probably felt that he had to. After the fact, we can wax ecstatic about the vastness of the new country, though at the time only a few philosophers gloried in the creeks and trees. We might wish that those folk who found themselves on the banks of the Delaware two hundred and fifty years ago had related to the environment like Thoreau or a crusading member of the Sierra Club, but they were peasants. The forests were enemies, strange and evil, existing only to be cleared. The forests caused the immediate invention of nothing—men do not work that way—but they did cause the selection and elaboration of old traditions through which the trees could be utilized—or rather, exploited, for wood was wasted and what was used was ripped out of natural shape and hidden. Then as now, the ash-tough American on the move felt that the physical environment was something to devastate. America to the newcomer, as Leo Marx has pointed out, was “both Eden and a howling desert,” a wilderness and a garden; the idea of wilderness produced fear, but the idea of the garden gave him strength, and the American “environment-buster” tore fearfully and optimistically through the land. The limitless spaces he faced had to be controlled to eliminate the fear and to realize the optimism. Great expanses of land had to be turned from wilderness into material culture; they had to be subdued by the surveyor’s chain and mile upon mile of fencing; they had to be claimed by buildings, tall, inharmonious signs of conquest dropped across the landscape—manmade forms spread out as far and lonesome as they could be, without leaving too much space between for the wilderness to slip in.

在构成新世界环境的各种因素中,土地供应是最明显的因素,也是推动规划突然改变的原因。特拉华河谷定居者的土地比他欧洲父辈的土地大得多;他可以把他的建筑和农场分散开;更重要的是,他可能觉得他必须这样做。在这之后,我们可以为新国家的辽阔而欣喜若狂,尽管当时只有少数哲学家为小溪和树木而陶醉。我们或许希望,二百五十多年前,发现自己置身特拉华河畔的那些人,能像梭罗或塞拉俱乐部的十字军成员一样与环境结缘,但他们是农民。森林是敌人,陌生而邪恶,存在的目的只是为了被砍伐。森林没有带来任何直接的发明——人类不是这样工作的——但它们确实促使人们选择并发展了古老的传统,通过这些传统,人们可以利用树木——或者更确切地说,是开发利用树木,因为木材被浪费了,用过的木材被撕掉自然的形状并隐藏起来。当时和现在一样,美国人在迁移的过程中,对自然环境的破坏也是不遗余力的。正如利奥.马克思所指的,对新来者来说,美国“既是伊甸园,又是咆哮的沙漠”,既是荒野,又是花园;荒野的概念让人恐惧,但花园的概念给人力量。他所面对的无限空间必须加以控制,以消除恐惧,实现乐观。大片土地必须从荒野变为物质文化;必须用测量员的铁链和一英里一英里的栅栏将其控制:必须用建筑物将其占领,高大而不和谐的征服标志横跨整个地貌,人造的形式尽可能地伸展开来,尽可能地孑然而立,不给荒野留下太多的空隙。

Transition can be read in the characteristic spatial arrangements of the Delaware Valley; there is a lingering sense of the tightness of the English or German peasant with his clustered, cooperative modes, but there is also the beginning and fulfillment of the dominant style of America, loose, worried, acquisitive individualism. Dispersion—separate buildings, separate holdings—is the major material manifestation of cultural response to the New World environment,and it has been from the beginning of European settlement. Jamestown was only fifteen years old when an English visitor complained that the buildings seemed scattered about. Three hundred and thirteen years later, Le Corbusier noted that the American desire for “a little garden, a little house, the assurance of freedom”—the capitalistic possession of a bit of land—had resulted in the failure of the American city and the American way of life. From the Delaware Valley westward go separate holdings where the nuclear family works for itself, where ownership is an end in itself, where noncooperative capitalism flourishes. The single farmstead, symbol of individualistic endeavor, is compatibly systematic with other segments of the culture; the constricted, unaccompanied solo singing, the literature demanding authority, the art and architecture stressing symmetry, the strict sex roles, the restrictive morality with its attendant modesty, guilt, and patrilocality, the politics of individual power, and the hope for upward mobility within what Henry Nash Smith calls “the fee-simple empire.”

从特拉华河谷特有的空间布局中可以读出过渡性痕迹;英国或德国农民的紧密感及其聚居、合作模式挥之不去,但美国的主流风格——松散、忧虑、获取性的个人主义——也在这里开始并实现。分散而又独立的建筑、独立的财产是面对新大陆环境的文化回应的主要物质表现形式,从欧洲人定居伊始就是如此。一位英国游客抱怨说,这里的建筑似乎分散在各处,詹姆斯镇只有十五年历史。三百一十三年后,勒柯布西耶指出,美国人对“小花园、小房子、自由的保证”的渴望——对一丁点土地的资本主义占有——导致了美国城市和美国生活方式的失败。从特拉华山谷向西走,是一个个独立的庄园,小家庭为自己工作,所有权本身就是目的,非合作的资本主义在这里蓬勃发展。单个农庄是个人主义努力的象征,它与文化中的其他部分相辅相成,如受限制的、无伴奏独唱、要求权威的文学、强调对称的艺术和建筑、严格的性别角色、限制性的道德及其附带的谦虚、内疚和父权制、个人权力政治以及在亨利.纳什.史密斯所说的”简单收费帝国”中向上流动的希望。

Individualism suggests conformity and breeds repetition. The irony of cultural freedom in America has not been better expressed than by D. H. Lawrence: masterless, the American is mastered; free, the American has conservatively chosen to restrict freedom. The land of the free is paradoxically not a land of endless variety. The critic might react differently to an eighteenth-century farmhouse and a modern rambler (and the old house is objectively assisted in its appeal by the soft edges that come with age and the subtlety that, as James Agee wrote, results from the attempt to achieve stark symmetry with less than perfect hand methods), but there are no more basic eighteenth-century farmhouse types in the Delaware Valley than there are different house models in many subdivisions. The colonial American would have had no more trouble finding the whitewashed kitchen in the home of an unknown contemporary than today’s suburbanite would have finding the knotty pine rec room in the split-level of a new neighbor.

个人主义意味着墨守成规,滋生重复。劳伦斯对美国文化自由的讽刺表达得淋漓尽致:无主的美国人被主宰;自由的美国人保守地选择限制自由。自相矛盾的是,自由的国度并不是一个无穷无尽多样性的国度。评论家可能会对十八世纪的农舍和现代平房产生不同的反应(老房子的吸引力客观上得益于岁月留下的柔和棱角,以及詹姆斯.艾吉述及的精妙之处,这是用不太完美的手工方法试图达到鲜明对称的结果),但特拉华河谷十八世纪农舍的基本类型并不多,就像许多住宅小区的不同户型一样。殖民地时期的美国人在无名的当代人家里找到粉刷过的厨房,不会比今天的郊区居民在新邻居家的分层房里找到一间松木娱乐室更难。

Books may not tell us, but buildings do. The eighteenth-century average guy in the Delaware Valley was an individualist but a conformist—a wary adventurer. He felt anxious in his adjustment to the changing times and chose to appear modern while acting conservatively. He cared more for economics than for aesthetics. He does not sound unfamiliar.

书籍可能不会告诉我们,但房屋会。十八世纪特拉华河谷的普通人是一个个人主义者,但也是一个循规蹈矩的人——一个警惕的冒险家。他在适应时代变迁的过程中感到焦虑不安,因此选择在保守的同时显得现代。他关心经济多于美学。他的故事听起来并不陌生。

参考文献

1) 吕江. 简述从建筑史学的视角看美国风土建筑的研究[J]. 建筑师, 2023, (06): 115-125.

2) 程梦稷. 民居的“语言”:亨利·格拉西《弗吉尼亚中部民居》评述[J]. 民间文化论坛, 2018, (03): 113-124.

附录

Vernacular Architecture: Critical and Primary Sources (Vol.1-4)

Editor: Howard Davis

London,NewYork:Bloomsbury Academic,2024.

《风土建筑:批判与基本的来源》(4卷本)

编者:霍华德·戴维斯

伦敦,纽约:布卢姆斯伯里学术出版社,2024

第1卷:分类学与地理学

第2卷:社会生活

第3卷:建造文化

第4卷:新兴都市风土

4卷本的《风土建筑:批判与基本的来源》于2024年出版,首次汇集了关于风土建筑和世界传统建筑文化研究的基础读物和代表性成果。从过去200年学术研究和历史文本的广泛来源,提供关于风土建筑领域的全面研究框架。在建立批判性阅读之外,将理论与当代专业实践联系起来。而建筑研究的关键核心和分类解释,对建筑环境、遗产研究和物质文化研究的当下课题至关重要。

这套书根据时间顺序分主题,反映智力、知识、观念的循序渐进,从乡村,浪漫主义和传统的解释,递进到当代跨学科的风土定义——将当代观点与关于城市爆炸性增长和全球城市未来的新学术研究走向联系在一起。风土问题不仅是建筑史学者关注的主题,也是专业建筑师、规划师和公众所关注的问题,风土是活着的传统。今人将从风土建筑中吸取智慧,应用于设计和社会批判。自2023年起开设的同济大学建筑城规学院研究生课程《西方现代风土建筑概论》,于2024年起围绕该最新的风土研究学术档案《风土建筑:批判与基本的来源》四卷本,根据其编撰带来的启发,增设风土研究关键性文献工作坊,工作内容为组织研究生对不限于该文献的经典风土研究篇目逐篇组织译介、分析和批判性评述,计划将工作坊成果在本平台辟专辑陆续推出,供广大学友交流学习,并在充分吸收读者反馈后结集出版。2025年该课程将由潘玥老师继续主持,欢迎在校学生和广大读者持续关注、留言、互动!

●Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc THE HABITATIONS OF MAN IN ALL AGES

●William Morris-ON THE LACK OF INCENTIVE TO LABOUR

●Lewis H. Morgan INTRODUCTION AND HOUSES AND HOUSELIFE

●Bronislaw Malinowski THE NATIVES OF THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS

●Le Corbusier TURNOVO

●Sibyl Moholy-Nagy NATIVE GENIUS IN ANONYMOUS ARCHITECTURE

●Bernard Rudofsky PREFACE, ARCHITECTURE WITHOUT ARCHITECTS

●Christian Norberg-Schulz MAN-MADE PLACE

●Martin Heidegger BUILDING DWELLING THINKING

●Christopher Alexander THE SELFCONSCIOUS PROCESS

●Paul Oliver HANDED DOWN ARCHITECTURE:TRADITION AND TRANSMISSION

●Henry Glassie EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CULTURAL PROCESS

●Ronald G. Knapp THE VARIETY OF CHINESE RURAL DWELLINGS

2024春季《西方现代风土建筑概论》课程讲座精彩回放请关注B站,下方点击收看:

●第三讲 历时思维与共时思维:19世纪以来的风土建筑遗产范型(一)

● 第七讲 风土的现象学维度——再读“没有建筑师的建筑”(一)

●第八讲 风土的现象学维度——再读“没有建筑师的建筑”(二)

……

周末快乐!

建筑遗产学刊(公众号)

微信平台:jzyc_ha(微信号)

官方网站:

https://jianzhuyichan.tongji.edu.cn/

《建筑遗产》学刊创刊于2016年,由中国科学院主管,中国科技出版传媒股份有限公司/同济大学主办,科学出版社出版,是我国历史建成物及其环境研究、保护与再生领域的第一本大型综合性专业期刊,国内外公开发行。

本刊公众号将继续秉承增强公众文化遗产保护理念,推进城乡文化资源整合利用的核心价值,以进一步提高公众普及度、学科引领性、专业渗透力为目标,不断带来一系列专业、优质的人文暖身阅读。

点击“阅读原文”进入“建筑遗产学刊”官网

点击“阅读原文”进入“建筑遗产学刊”官网

原文始发于微信公众号(建筑遗产学刊):亨利•格拉西《十八世纪文化进程》

规划问道

规划问道