以利物浦为代表的英国后工业时代城市,在面临疫情危机时显现了产业结构脆弱、失业率高涨、心理问题凸显、数据管控不力等诸多城市问题。利物浦大学赫塞尔廷公共政策实践与场所研究所所长Mark Boyle教授认为,城市韧性不光体现在其恢复力上,更重要的是以此为契机进行跨越升级。

我们应该作好与病毒长期共存的准备,在积极抗疫的同时前瞻性地思考灾后恢复问题;并且开始重视基础经济的价值,深入思考对其再投入的必要策略,以此助力推进可持续的去工业化及城市更新政策。

本期嘉宾 | Mark Boyle 教授

Mark Boyle教授是利物浦大学赫塞尔廷公共政策实践与场所研究所所长。该研究所汇集了政策决策者和实践者的专业知识,以支持城市和区域更新过程中的可持续和包容性发展。其主要研究范围包括利物浦地区。

Professor Mark Boyle is a trained human geographer, his research pivots around urban studies and urban policy. In 2017, he was ranked in the top 50 most productive scholars in Geography and Urban Studies in the world across the preceding 20 years. He is also editor in chief of the Journal Taylor and Francis Journal Space and Polity.

目前赫塞尔廷研究所正在积极开展COVID-19相关研究:即赫塞尔廷研究所政策简报。新冠疫情是利物浦地区当代所面临的最严峻的公共政策挑战之一。我们集结了校内和整个利物浦地区的专业力量,与利物浦市区联合管理局在知识与最佳案例传播、专业知识转化方面进行合作,以减缓目前的健康危机及其社会、经济和环境的后续影响, 从而帮助城市区域更好地重建。

毫无疑问COVID-19将会改变世界。此前没有任何一场危机能影响到全球80亿人口,涉及每一个经济部门、每一个社会阶层、每一个国家——英国首相已被确诊,目前正在重症监护中(注:采访日期4月8日),在这场灾害中无人能够幸免。这是一项重要的世界性历史事件,并将定义新一代的公共政策和城市政策。

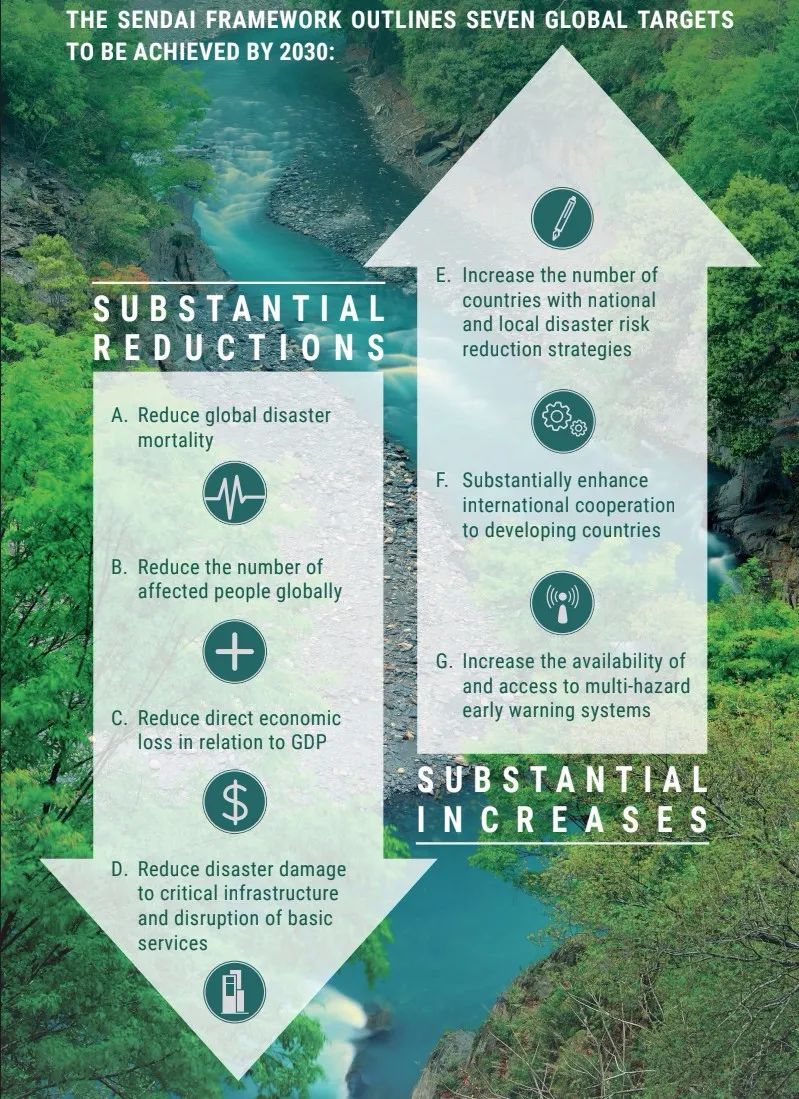

联合国《仙台减少灾害风险框架》谈到要更好地恢复和更好地重建。这应该被视作世界发展前进所遵循的箴言。我们需要积极地面对COVID-19及其带来的后续影响,还要保证在面对COVID-20、COVID-21或其他重大自然、人为灾害时能够更好地保护自己。人们所面临的威胁正在增加,过去一生一次的事件现在可能会在十年内发生三次!

《仙台减少灾害风险框架》目标

图片来源:https://www.undrr.org/

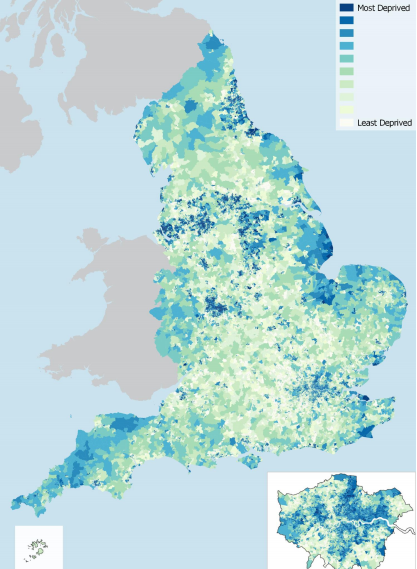

利物浦这样的城市,与英国其他地区(特别是伦敦)相比,在面对危机时还没有足够的韧性。我们在去工业化后的复兴与恢复计划中只走了一段路——地区在全英“多重剥夺指数“(衡量地区相对贫困水平的指标)中排名靠前;而人口健康水平较全国其他地方相比却较为落后。COVID-19无情地利用了我们的弱点,我们必须坚定不移地进行更好的重建。该如何解释“更好的重建”呢?

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019-mapping-resources#indices-of-deprivation-2019-local-authority-dashboard

“韧性”的概念是减少灾害风险的核心。但建立韧性到底意味着什么?学术界与业界对它的理解各不相同。这一点很重要:框架在塑造韧性构建策略方面起着至关重要的作用,而这些政策之后又会被解读与落实。我用“弹性政治”一词来指代在面对灾难及潜在风险、危害的背景下,因关于如何建立韧性的不同观点而导致的不同后果。在以增强韧性的名义重建城市时,城市领导者们需要认识到,他们正在为自己努力创造的未来作出政治选择。

图片来源:https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/heseltine-institute/

如何识别城市经济的脆弱点,在使之恢复平衡方面,需要关注哪些关键领域?

图片来源:网络

2020年1月份,世界经济论坛于成立50周年之际发布了一份关于恢复性和伦理资本主义的新版《达沃斯宣言》。在此背景下,我们为什么要认识到“关键工作者” (key worker)和“基础经济”(foundation economy)在增强城市韧性中的重要性?

人们理所当然地认为,资本主义是一个强大的经济体系,可以激发创业精神并推动经济增长,消除数十亿的贫困。但同时,市场经济也面临着诸多问题。资本主义正在制造巨大的不平等现象,这种不平等在许多国家中以政治民粹主义的形式表现出来——包括英国“脱欧”运动的兴起。

“基础经济”(社会保障、医疗和教育)意味着当城市回归基本要素时,必须保障一定数量的就业支撑以确保城市的运转。这些工作通常不会是光鲜亮丽,或对上层阶级有特别吸引力的。而是城市赖以生存的一些最基本的服务、功能和经济活动。其中包括超市、物流、医院、社会保障和社会关怀等行业。

当我们隔离在家时,这些关键工作者们(医疗保健、教育或警察等重要服务行业的工作人员)仍然冒着生命危险在前线工作。当下已开始显示出基础经济应有的样子,并使我们认识到在紧急危机中维持城市运转所需的所有基本元素。我希望这次危机过后,人们会更加尊重基础经济和关键工作者,也应当给予他们适当的酬劳及回报。

Thank you for the kind invitation to speak today. I hope you are all well at Suzhou, and congratulate the Urban and Environmental Studies University Research Centre and indeed all your colleagues at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University for the really great work you are doing around the COVID-19 outbreak and its aftershocks.

As you know, at the Heseltine Institute we too are actively COVID-19: Heseltine Institute Policy Briefs. COVID-19 presents one of the greatest public policy challenges Liverpool City Region has faced in a generation. We are drawing upon expertise from within the University of Liverpool and indeed across the Liverpool City Region, in collaboration with the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority to disseminate knowledge, best practices and translational research expertise to help mitigate the present health crisis and its social, economic and environmental aftershocks, as to help the city-region build back better. You can find these at: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/heseltine-institute/covid-19policybriefs/

COVID-19 is going to change the world. No question. There has been no crisis that has affected the world’s entire 8 billion population – every economic sector, every strata of society, every country – the prime minister of Britain has been diagnosed with COVID-19 and is currently in intensive care (* interview on 8th April). No one is spared. The pandemic is a significant world historical event that is going to define a new generation of public policy and urban policy.

Meanwhile, it is not wise to think about COVID-19 being a temporary blip or a temporary set back and that we can just go back to normal life after. It is something far more instructive; it requires the whole world to reflect upon the model of economic development that is powering the world economy – we really need to think about the sustainability of this model. A small virus has shown how fragile the whole interconnected global economy really is. The way we do things needs to change moving forward.

There is a lot of work to be done in terms of the immediate emergency, including dealing with the health and health care crisis, reopening society following lockdown and returning to work in the coming months. But it is also crucial that we learn longer term lessons; once we get over this initial period of crisis and emergency we will need to build more resilient economies and cities.

The United Nations Sendai Disaster Risk Reduction Framework talks about ‘bouncing back better’ and ‘building back better’, and that ought to be the mantra of the world moving forward. We need to remediate the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftershocks, but it would be criminal if we do not also start thinking now about how to better protect ourselves in the event of a COVID-20 or COVID-21 or indeed any other major natural or human induced hazard. Threats are increasing and once in a lifetime events are now occurring three times in a decade!

Resilience is increasingly interpreted as more than simply helping urban systems achieve homeostasis, what will be the main challenges of speedy and sustained urban recovery, particularly in the post-industrial period?

Cities like Liverpool are perhaps not as resilient as other parts of the UK, especially London. We are only part way through a regeneration and recovery programme after deindustrialization – we still suffer high levels of multiple deprivation and our population has poorer levels of health than the rest of the country. COVID-19 has ruthlessly exploited our vulnerabilities. We need to build back better for sure. But what does that mean? Who owns the term build back better?

The concept of ‘resilience’ is central to disaster risk reduction. But what does building resilience actually mean? Resilience is understood variously in both academic and practitioner communities. This matters: framings play a crucial role in shaping the kinds of resilience building strategies which might be imagined and enacted. I use the term ‘resilience politics’ to refer to the differential consequences of different perspectives on how to build resilience in the wake of a disaster and against the backdrop of a looming risk or hazard. When rebuilding cities in the name of strengthening resilience, civic leaders need to recognize that they are making political choices about the kind of future they are working to create.

Four ideas are in circulation: whilst not mutually exclusive each does focus attention and effort in distinctive ways.

Resilience as robustness: focusing upon the amount of shock a system can absorb and continue to function effectively and prioritising strengthening the resistance of systems to external disturbances,

Resilience as recovery: focusing upon the capacity of systems to return to a steady initial equilibrium steady state after a shock and prioritising solutions which help systems heal and repair faster

Resilience as reform: focusing upon the capacity of systems after a shock to adapt and evolve so that they are stronger than before and prioritising reform within the same politico-institutional norm.

Resilience as reconstruction: focusing upon the necessity of reconfiguring systems root and branch after a shock and prioritising politico-institutional transformation as the only enduring solution.

Each plays to a different resilience politics register. Clearly, robustness, recovery, reform and reconstruction all have strengths and weaknesses in different contexts. We need to decide which pathway we want to take.

A common misconception about natural disasters is that populations most at risk are simply those unlucky enough to have been born in parts of the world where nature’s extremes are most manifest. Increasingly, it is being recognized that, whilst exposure to natural hazards is important, ultimately it is society that puts people at increased risk and, therefore, that solutions to natural hazards need to tackle the root causes of the social production of vulnerability to hazard events.

And so the formula Risk = Hazard × Vulnerability (R = H × V) has become of central importance in Hazards Research.

The University of Liverpool is currently funding the Heseltine Institute to undertake work on economic vulnerability. We are looking at which sectors, communities, households and areas in the city are most vulnerable and at risk from the economic fall out of COVID-19. We are using the United Nations University’s (UNU) definition of vulnerability in the research.

The UNU begins with the formula R=H ×V, but then breaks down vulnerability into three component parts: degree of susceptibility to hazards (likelihood of suffering harm), capacity to cope with hazards (capacity to mitigate the impact of hazards when they do occur), and ability to plan ahead to adapt to natural extremes (ability to minimize the degree to which exposure to hazards is increased by prior poor human decision making).

According to UNU, social, economic, cultural, and political processes determine a society’s degree of susceptibility, coping capacity, and ability to adapt.

Take Liverpool for example. As a coastal city and destination for tourism, Liverpool attracts many visitors, retail and hospitality are very significant sectors. We expect that these will take a long time to recover from COVID-19 which makes the city therefore more vulnerable. Liverpool also has a high unemployment rate and those people who find it difficult to get into the labour market are going to be especially vulnerable now, because the competition for jobs is going to be even more severe than before.

We also concerned about the interruption of supply chains – can companies source the supplies and components they need to allow them to manufacture goods and provide services as normal. The fact that Liverpool ranks highly in multiple deprivation indices across Britain gives us particular concern. If people have low income and sparse resources (savings, wealth) a period of unemployment is going to be very distressing for them and their family.

All of this matter – being exposed to the Coronovirus is only part of the story.

Capitalism is rightly considered to be a powerful economic system that energises entrepreneurship and catalysis economic growth. Markets have taken billions of poverty. But market economies are beset with problems too. There is a recognition that capitalism is creating huge inequalities that are manifesting themselves in the form of political populism in many countries – including in our own country with the rise of the Brexit movement.

What for example has led to Trump (US), Hofer (Austria), Wilders (Netherlands), Hoffer/Kurz (Austria), Orbán (Hungary), Le Pen (France), Bolsonaro (Brazil), Syriza (Greece), Podemos (Spain)? The global economy is also causing huge damage to the environment as our climate and ecological crisis reveals.

I think the Davos World Economic Forum is recognizing that if capitalism is going to survive, it needs to up its game and more inclusive and clean growth is going to be the key to the future. WEF are starting to talk about ‘stakeholder capitalism’ as a new form of capitalism.

It’s not particularly new. The United States in the 1940s-1960s started to look at the impact of companies not just on shareholders but also on the wide variety of stakeholders they engage. There is a growing recognition that there is a need for a triple bottom line with environmental, social and economic measures defining a company’s success, not just shareholders’ returns and profits.

John Fullerton, an ex-Managing Director of JP Morgan, talks about ‘regenerative capitalism’. It’s the same kind of idea – making capitalism mimic the ecological systems active in the world rather than cutting across those systems, and trying to build a system that is in harmony with the environment and in harmony with human needs.

The idea of the ‘foundational economy’ is also doing the rounds, stripping the city back to its basic elements, and recognizing that a certain number of jobs have to be done for a city to function. These are often not the jobs that would be glamorous or particularly attractive to the higher class. They are often jobs in essential services, essential functions, and essential economic activities – for example in supermarkets, logistics, hospitals, social securities and social cares.

Currently key workers are working and risking their lives whereas the rest of the professional classes are locked down safely at home. COVID-19 is starting to show what the foundational economy looks like and why it matters and needs to be better supported. I’m hoping that after this crisis there will be a new respect for the foundational economy and for its key workers, and there will be proper remuneration and payment for these workers.

-End-

原文始发于微信公众号(国际城市规划):全球汇 | 全球疫情下,英国后工业的脆弱性和资本主义新伦理

规划问道

规划问道